|

Reference documentation for deal.II version 9.3.3

|

|

Reference documentation for deal.II version 9.3.3

|

This tutorial depends on step-24.

| Table of contents | |

|---|---|

This program grew out of a student project by Ivan Christov at Texas A&M University. Most of the work for this program is by him.

The goal of this program is to solve the sine-Gordon soliton equation in 1, 2 or 3 spatial dimensions. The motivation for solving this equation is that very little is known about the nature of the solutions in 2D and 3D, even though the 1D case has been studied extensively.

Rather facetiously, the sine-Gordon equation's moniker is a pun on the so-called Klein-Gordon equation, which is a relativistic version of the Schrödinger equation for particles with non-zero mass. The resemblance is not just superficial, the sine-Gordon equation has been shown to model some unified-field phenomena such as interaction of subatomic particles (see, e.g., Perring & Skyrme in Nuclear Physics 31) and the Josephson (quantum) effect in superconductor junctions (see, e.g., http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_Josephson_junction). Furthermore, from the mathematical standpoint, since the sine-Gordon equation is "completely integrable," it is a candidate for study using the usual methods such as the inverse scattering transform. Consequently, over the years, many interesting solitary-wave, and even stationary, solutions to the sine-Gordon equation have been found. In these solutions, particles correspond to localized features. For more on the sine-Gordon equation, the inverse scattering transform and other methods for finding analytical soliton equations, the reader should consult the following "classical" references on the subject: G. L. Lamb's Elements of Soliton Theory (Chapter 5, Section 2) and G. B. Whitham's Linear and Nonlinear Waves (Chapter 17, Sections 10-13).

The sine-Gordon initial-boundary-value problem (IBVP) we wish to solve consists of the following equations:

\begin{eqnarray*} u_{tt}-\Delta u &=& -\sin(u) \quad\mbox{for}\quad (x,t) \in \Omega \times (t_0,t_f],\\ {\mathbf n} \cdot \nabla u &=& 0 \quad\mbox{for}\quad (x,t) \in \partial\Omega \times (t_0,t_f],\\ u(x,t_0) &=& u_0(x). \end{eqnarray*}

It is a nonlinear equation similar to the wave equation we discussed in step-23 and step-24. We have chosen to enforce zero Neumann boundary conditions in order for waves to reflect off the boundaries of our domain. It should be noted, however, that Dirichlet boundary conditions are not appropriate for this problem. Even though the solutions to the sine-Gordon equation are localized, it only makes sense to specify (Dirichlet) boundary conditions at x=\pm\infty, otherwise either a solution does not exist or only the trivial solution u=0 exists.

However, the form of the equation above is not ideal for numerical discretization. If we were to discretize the second-order time derivative directly and accurately, then we would need a large stencil (i.e., several time steps would need to be kept in the memory), which could become expensive. Therefore, in complete analogy to what we did in step-23 and step-24, we split the second-order (in time) sine-Gordon equation into a system of two first-order (in time) equations, which we call the split, or velocity, formulation. To this end, by setting v = u_t, it is easy to see that the sine-Gordon equation is equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*} u_t - v &=& 0,\\ v_t - \Delta u &=& -\sin(u). \end{eqnarray*}

Now, we can discretize the split formulation in time using the \theta-method, which has a stencil of only two time steps. By choosing a \theta\in [0,1], the latter discretization allows us to choose from a continuum of schemes. In particular, if we pick \theta=0 or \theta=1, we obtain the first-order accurate explicit or implicit Euler method, respectively. Another important choice is \theta=\frac{1}{2}, which gives the second-order accurate Crank-Nicolson scheme. Henceforth, a superscript n denotes the values of the variables at the n^{\mathrm{th}} time step, i.e. at t=t_n \dealcoloneq n k, where k is the (fixed) time step size. Thus, the split formulation of the time-discretized sine-Gordon equation becomes

\begin{eqnarray*} \frac{u^n - u^{n-1}}{k} - \left[\theta v^n + (1-\theta) v^{n-1}\right] &=& 0,\\ \frac{v^n - v^{n-1}}{k} - \Delta\left[\theta u^n + (1-\theta) u^{n-1}\right] &=& -\sin\left[\theta u^n + (1-\theta) u^{n-1}\right]. \end{eqnarray*}

We can simplify the latter via a bit of algebra. Eliminating v^n from the first equation and rearranging, we obtain

\begin{eqnarray*} \left[ 1-k^2\theta^2\Delta \right] u^n &=& \left[ 1+k^2\theta(1-\theta)\Delta\right] u^{n-1} + k v^{n-1} - k^2\theta\sin\left[\theta u^n + (1-\theta) u^{n-1}\right],\\ v^n &=& v^{n-1} + k\Delta\left[ \theta u^n + (1-\theta) u^{n-1}\right] - k\sin\left[ \theta u^n + (1-\theta) u^{n-1} \right]. \end{eqnarray*}

It may seem as though we can just proceed to discretize the equations in space at this point. While this is true for the second equation (which is linear in v^n), this would not work for all \theta since the first equation above is nonlinear. Therefore, a nonlinear solver must be implemented, then the equations can be discretized in space and solved.

To this end, we can use Newton's method. Given the nonlinear equation F(u^n) = 0, we produce successive approximations to u^n as follows:

\begin{eqnarray*} \mbox{ Find } \delta u^n_l \mbox{ s.t. } F'(u^n_l)\delta u^n_l = -F(u^n_l) \mbox{, set } u^n_{l+1} = u^n_l + \delta u^n_l. \end{eqnarray*}

The iteration can be initialized with the old time step, i.e. u^n_0 = u^{n-1}, and eventually it will produce a solution to the first equation of the split formulation (see above). For the time discretization of the sine-Gordon equation under consideration here, we have that

\begin{eqnarray*} F(u^n_l) &=& \left[ 1-k^2\theta^2\Delta \right] u^n_l - \left[ 1+k^2\theta(1-\theta)\Delta\right] u^{n-1} - k v^{n-1} + k^2\theta\sin\left[\theta u^n_l + (1-\theta) u^{n-1}\right],\\ F'(u^n_l) &=& 1-k^2\theta^2\Delta + k^2\theta^2\cos\left[\theta u^n_l + (1-\theta) u^{n-1}\right]. \end{eqnarray*}

Notice that while F(u^n_l) is a function, F'(u^n_l) is an operator.

With hindsight, we choose both the solution and the test space to be H^1(\Omega). Hence, multiplying by a test function \varphi and integrating, we obtain the following variational (or weak) formulation of the split formulation (including the nonlinear solver for the first equation) at each time step:

\begin{eqnarray*} &\mbox{ Find}& \delta u^n_l \in H^1(\Omega) \mbox{ s.t. } \left( F'(u^n_l)\delta u^n_l, \varphi \right)_{\Omega} = -\left(F(u^n_l), \varphi \right)_{\Omega} \;\forall\varphi\in H^1(\Omega), \mbox{ set } u^n_{l+1} = u^n_l + \delta u^n_l,\; u^n_0 = u^{n-1}.\\ &\mbox{ Find}& v^n \in H^1(\Omega) \mbox{ s.t. } \left( v^n, \varphi \right)_{\Omega} = \left( v^{n-1}, \varphi \right)_{\Omega} - k\theta\left( \nabla u^n, \nabla\varphi \right)_{\Omega} - k (1-\theta)\left( \nabla u^{n-1}, \nabla\varphi \right)_{\Omega} - k\left(\sin\left[ \theta u^n + (1-\theta) u^{n-1} \right], \varphi \right)_{\Omega} \;\forall\varphi\in H^1(\Omega). \end{eqnarray*}

Note that the we have used integration by parts and the zero Neumann boundary conditions on all terms involving the Laplacian operator. Moreover, F(\cdot) and F'(\cdot) are as defined above, and (\cdot,\cdot)_{\Omega} denotes the usual L^2 inner product over the domain \Omega, i.e. (f,g)_{\Omega} = \int_\Omega fg \,\mathrm{d}x. Finally, notice that the first equation is, in fact, the definition of an iterative procedure, so it is solved multiple times during each time step until a stopping criterion is met.

Using the Finite Element Method, we discretize the variational formulation in space. To this end, let V_h be a finite-dimensional H^1(\Omega)-conforming finite element space ( \mathrm{dim}\, V_h = N < \infty) with nodal basis \{\varphi_1,\ldots,\varphi_N\}. Now, we can expand all functions in the weak formulation (see above) in terms of the nodal basis. Henceforth, we shall denote by a capital letter the vector of coefficients (in the nodal basis) of a function denoted by the same letter in lower case; e.g., u^n = \sum_{i=1}^N U^n_i \varphi_i where U^n \in {R}^N and u^n \in H^1(\Omega). Thus, the finite-dimensional version of the variational formulation requires that we solve the following matrix equations at each time step:

\begin{eqnarray*} F_h'(U^{n,l})\delta U^{n,l} &=& -F_h(U^{n,l}), \qquad U^{n,l+1} = U^{n,l} + \delta U^{n,l}, \qquad U^{n,0} = U^{n-1}; \\ MV^n &=& MV^{n-1} - k \theta AU^n -k (1-\theta) AU^{n-1} - k S(u^n,u^{n-1}). \end{eqnarray*}

Above, the matrix F_h'(\cdot) and the vector F_h(\cdot) denote the discrete versions of the gadgets discussed above, i.e.,

\begin{eqnarray*} F_h(U^{n,l}) &=& \left[ M+k^2\theta^2A \right] U^{n,l} - \left[ M-k^2\theta(1-\theta)A \right] U^{n-1} - k MV^{n-1} + k^2\theta S(u^n_l, u^{n-1}),\\ F_h'(U^{n,l}) &=& M+k^2\theta^2A + k^2\theta^2N(u^n_l,u^{n-1}) \end{eqnarray*}

Again, note that the first matrix equation above is, in fact, the definition of an iterative procedure, so it is solved multiple times until a stopping criterion is met. Moreover, M is the mass matrix, i.e. M_{ij} = \left( \varphi_i,\varphi_j \right)_{\Omega}, A is the Laplace matrix, i.e. A_{ij} = \left( \nabla \varphi_i, \nabla \varphi_j \right)_{\Omega}, S is the nonlinear term in the equation that defines our auxiliary velocity variable, i.e. S_j(f,g) = \left( \sin\left[ \theta f + (1-\theta) g\right], \varphi_j \right)_{\Omega}, and N is the nonlinear term in the Jacobian matrix of F(\cdot), i.e. N_{ij}(f,g) = \left( \cos\left[ \theta f + (1-\theta) g\right]\varphi_i, \varphi_j \right)_{\Omega}.

What solvers can we use for the first equation? Let's look at the matrix we have to invert:

(M+k^2\theta^2(A + N))_{ij} = \int_\Omega (1+k^2\theta^2 \cos \alpha) \varphi_i\varphi_j \; dx + k^2 \theta^2 \int_\Omega \nabla\varphi_i\nabla\varphi_j \; dx,

for some \alpha that depends on the present and previous solution. First, note that the matrix is symmetric. In addition, if the time step k is small enough, i.e. if k\theta<1, then the matrix is also going to be positive definite. In the program below, this will always be the case, so we will use the Conjugate Gradient method together with the SSOR method as preconditioner. We should keep in mind, however, that this will fail if we happen to use a bigger time step. Fortunately, in that case the solver will just throw an exception indicating a failure to converge, rather than silently producing a wrong result. If that happens, then we can simply replace the CG method by something that can handle indefinite symmetric systems. The GMRES solver is typically the standard method for all "bad" linear systems, but it is also a slow one. Possibly better would be a solver that utilizes the symmetry, such as, for example, SymmLQ, which is also implemented in deal.II.

This program uses a clever optimization over step-23 and step-24: If you read the above formulas closely, it becomes clear that the velocity V only ever appears in products with the mass matrix. In step-23 and step-24, we were, therefore, a bit wasteful: in each time step, we would solve a linear system with the mass matrix, only to multiply the solution of that system by M again in the next time step. This can, of course, be avoided, and we do so in this program.

There are a few analytical solutions for the sine-Gordon equation, both in 1D and 2D. In particular, the program as is computes the solution to a problem with a single kink-like solitary wave initial condition. This solution is given by Leibbrandt in Phys. Rev. Lett. 41(7), and is implemented in the ExactSolution class.

It should be noted that this closed-form solution, strictly speaking, only holds for the infinite-space initial-value problem (not the Neumann initial-boundary-value problem under consideration here). However, given that we impose zero Neumann boundary conditions, we expect that the solution to our initial-boundary-value problem would be close to the solution of the infinite-space initial-value problem, if reflections of waves off the boundaries of our domain do not occur. In practice, this is of course not the case, but we can at least assume that this were so.

The constants \vartheta and \lambda in the 2D solution and \vartheta, \phi and \tau in the 3D solution are called the Bäcklund transformation parameters. They control such things as the orientation and steepness of the kink. For the purposes of testing the code against the exact solution, one should choose the parameters so that the kink is aligned with the grid.

The solutions that we implement in the ExactSolution class are these:

In 1D:

u(x,t) = -4 \arctan\left[ \frac{m}{\sqrt{1-m^2}} \frac{\sin\left(\sqrt{1-m^2}t+c_2\right)} {\cosh\left(mx+c_1\right)} \right],

where we choose m=\frac 12, c_1=c_2=0.

In 1D, more interesting analytical solutions are known. Many of them are listed on http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Sine-GordonEquation.html .

In 2D:

u(x,y,t) = 4 \arctan \left[a_0 e^{s\xi}\right],

where \xi is defined as

\xi = x \cos\vartheta + \sin(\vartheta) (y\cosh\lambda + t\sinh \lambda),

and where we choose \vartheta=\frac \pi 4, \lambda=a_0=s=1.

u(x,y,z,t) = 4 \arctan \left[c_0 e^{s\xi}\right],

where \xi is defined as\xi = x \cos\vartheta + y \sin \vartheta \cos\phi + \sin \vartheta \sin\phi (z\cosh\tau + t\sinh \tau),

and where we choose \vartheta=\phi=\frac{\pi}{4}, \tau=c_1=s=1.Since it makes it easier to play around, the InitialValues class that is used to set — surprise! — the initial values of our simulation simply queries the class that describes the exact solution for the value at the initial time, rather than duplicating the effort to implement a solution function.

For an explanation of the include files, the reader should refer to the example programs step-1 through step-4. They are in the standard order, which is base – lac – grid – dofs – fe – numerics (since each of these categories roughly builds upon previous ones), then a few C++ headers for file input/output and string streams.

The last step is as in all previous programs:

SineGordonProblem class templateThe entire algorithm for solving the problem is encapsulated in this class. As in previous example programs, the class is declared with a template parameter, which is the spatial dimension, so that we can solve the sine-Gordon equation in one, two or three spatial dimensions. For more on the dimension-independent class-encapsulation of the problem, the reader should consult step-3 and step-4.

Compared to step-23 and step-24, there isn't anything newsworthy in the general structure of the program (though there is of course in the inner workings of the various functions!). The most notable difference is the presence of the two new functions compute_nl_term and compute_nl_matrix that compute the nonlinear contributions to the system matrix and right-hand side of the first equation, as discussed in the Introduction. In addition, we have to have a vector solution_update that contains the nonlinear update to the solution vector in each Newton step.

As also mentioned in the introduction, we do not store the velocity variable in this program, but the mass matrix times the velocity. This is done in the M_x_velocity variable (the "x" is intended to stand for "times").

Finally, the output_timestep_skip variable stores the number of time steps to be taken each time before graphical output is to be generated. This is of importance when using fine meshes (and consequently small time steps) where we would run lots of time steps and create lots of output files of solutions that look almost the same in subsequent files. This only clogs up our visualization procedures and we should avoid creating more output than we are really interested in. Therefore, if this variable is set to a value n bigger than one, output is generated only every nth time step.

In the following two classes, we first implement the exact solution for 1D, 2D, and 3D mentioned in the introduction to this program. This space-time solution may be of independent interest if one wanted to test the accuracy of the program by comparing the numerical against the analytic solution (note however that the program uses a finite domain, whereas these are analytic solutions for an unbounded domain). This may, for example, be done using the VectorTools::integrate_difference function. Note, again (as was already discussed in step-23), how we describe space-time functions as spatial functions that depend on a time variable that can be set and queried using the FunctionTime::set_time() and FunctionTime::get_time() member functions of the FunctionTime base class of the Function class.

In the second part of this section, we provide the initial conditions. We are lazy (and cautious) and don't want to implement the same functions as above a second time. Rather, if we are queried for initial conditions, we create an object ExactSolution, set it to the correct time, and let it compute whatever values the exact solution has at that time:

SineGordonProblem classLet's move on to the implementation of the main class, as it implements the algorithm outlined in the introduction.

This is the constructor of the SineGordonProblem class. It specifies the desired polynomial degree of the finite elements, associates a DoFHandler to the triangulation object (just as in the example programs step-3 and step-4), initializes the current or initial time, the final time, the time step size, and the value of \theta for the time stepping scheme. Since the solutions we compute here are time-periodic, the actual value of the start-time doesn't matter, and we choose it so that we start at an interesting time.

Note that if we were to chose the explicit Euler time stepping scheme ( \theta = 0), then we must pick a time step k \le h, otherwise the scheme is not stable and oscillations might arise in the solution. The Crank-Nicolson scheme ( \theta = \frac{1}{2}) and the implicit Euler scheme ( \theta=1) do not suffer from this deficiency, since they are unconditionally stable. However, even then the time step should be chosen to be on the order of h in order to obtain a good solution. Since we know that our mesh results from the uniform subdivision of a rectangle, we can compute that time step easily; if we had a different domain, the technique in step-24 using GridTools::minimal_cell_diameter would work as well.

This function creates a rectangular grid in dim dimensions and refines it several times. Also, all matrix and vector members of the SineGordonProblem class are initialized to their appropriate sizes once the degrees of freedom have been assembled. Like step-24, we use MatrixCreator functions to generate a mass matrix M and a Laplace matrix A and store them in the appropriate variables for the remainder of the program's life.

This function assembles the system matrix and right-hand side vector for each iteration of Newton's method. The reader should refer to the Introduction for the explicit formulas for the system matrix and right-hand side.

Note that during each time step, we have to add up the various contributions to the matrix and right hand sides. In contrast to step-23 and step-24, this requires assembling a few more terms, since they depend on the solution of the previous time step or previous nonlinear step. We use the functions compute_nl_matrix and compute_nl_term to do this, while the present function provides the top-level logic.

First we assemble the Jacobian matrix F'_h(U^{n,l}), where U^{n,l} is stored in the vector solution for convenience.

Next we compute the right-hand side vector. This is just the combination of matrix-vector products implied by the description of -F_h(U^{n,l}) in the introduction.

This function computes the vector S(\cdot,\cdot), which appears in the nonlinear term in both equations of the split formulation. This function not only simplifies the repeated computation of this term, but it is also a fundamental part of the nonlinear iterative solver that we use when the time stepping is implicit (i.e. \theta\ne 0). Moreover, we must allow the function to receive as input an "old" and a "new" solution. These may not be the actual solutions of the problem stored in old_solution and solution, but are simply the two functions we linearize about. For the purposes of this function, let us call the first two arguments w_{\mathrm{old}} and w_{\mathrm{new}} in the documentation of this class below, respectively.

As a side-note, it is perhaps worth investigating what order quadrature formula is best suited for this type of integration. Since \sin(\cdot) is not a polynomial, there are probably no quadrature formulas that can integrate these terms exactly. It is usually sufficient to just make sure that the right hand side is integrated up to the same order of accuracy as the discretization scheme is, but it may be possible to improve on the constant in the asymptotic statement of convergence by choosing a more accurate quadrature formula.

Once we re-initialize our FEValues instantiation to the current cell, we make use of the get_function_values routine to get the values of the "old" data (presumably at t=t_{n-1}) and the "new" data (presumably at t=t_n) at the nodes of the chosen quadrature formula.

Now, we can evaluate \int_K \sin\left[\theta w_{\mathrm{new}} + (1-\theta) w_{\mathrm{old}}\right] \,\varphi_j\,\mathrm{d}x using the desired quadrature formula.

We conclude by adding up the contributions of the integrals over the cells to the global integral.

This is the second function dealing with the nonlinear scheme. It computes the matrix N(\cdot,\cdot), which appears in the nonlinear term in the Jacobian of F(\cdot). Just as compute_nl_term, we must allow this function to receive as input an "old" and a "new" solution, which we again call w_{\mathrm{old}} and w_{\mathrm{new}} below, respectively.

Again, first we re-initialize our FEValues instantiation to the current cell.

Then, we evaluate \int_K \cos\left[\theta w_{\mathrm{new}} + (1-\theta) w_{\mathrm{old}}\right]\, \varphi_i\, \varphi_j\,\mathrm{d}x using the desired quadrature formula.

Finally, we add up the contributions of the integrals over the cells to the global integral.

As discussed in the Introduction, this function uses the CG iterative solver on the linear system of equations resulting from the finite element spatial discretization of each iteration of Newton's method for the (nonlinear) first equation of the split formulation. The solution to the system is, in fact, \delta U^{n,l} so it is stored in solution_update and used to update solution in the run function.

Note that we re-set the solution update to zero before solving for it. This is not necessary: iterative solvers can start from any point and converge to the correct solution. If one has a good estimate about the solution of a linear system, it may be worthwhile to start from that vector, but as a general observation it is a fact that the starting point doesn't matter very much: it has to be a very, very good guess to reduce the number of iterations by more than a few. It turns out that for this problem, using the previous nonlinear update as a starting point actually hurts convergence and increases the number of iterations needed, so we simply set it to zero.

The function returns the number of iterations it took to converge to a solution. This number will later be used to generate output on the screen showing how many iterations were needed in each nonlinear iteration.

This function outputs the results to a file. It is pretty much identical to the respective functions in step-23 and step-24:

This function has the top-level control over everything: it runs the (outer) time-stepping loop, the (inner) nonlinear-solver loop, and outputs the solution after each time step.

To acknowledge the initial condition, we must use the function u_0(x) to compute U^0. To this end, below we will create an object of type InitialValues; note that when we create this object (which is derived from the Function class), we set its internal time variable to t_0, to indicate that the initial condition is a function of space and time evaluated at t=t_0.

Then we produce U^0 by projecting u_0(x) onto the grid using VectorTools::project. We have to use the same construct using hanging node constraints as in step-21: the VectorTools::project function requires a hanging node constraints object, but to be used we first need to close it:

For completeness, we output the zeroth time step to a file just like any other time step.

Now we perform the time stepping: at every time step we solve the matrix equation(s) corresponding to the finite element discretization of the problem, and then advance our solution according to the time stepping formulas we discussed in the Introduction.

At the beginning of each time step we must solve the nonlinear equation in the split formulation via Newton's method — i.e. solve for \delta U^{n,l} then compute U^{n,l+1} and so on. The stopping criterion for this nonlinear iteration is that \|F_h(U^{n,l})\|_2 \le 10^{-6} \|F_h(U^{n,0})\|_2. Consequently, we need to record the norm of the residual in the first iteration.

At the end of each iteration, we output to the console how many linear solver iterations it took us. When the loop below is done, we have (an approximation of) U^n.

Upon obtaining the solution to the first equation of the problem at t=t_n, we must update the auxiliary velocity variable V^n. However, we do not compute and store V^n since it is not a quantity we use directly in the problem. Hence, for simplicity, we update MV^n directly:

Oftentimes, in particular for fine meshes, we must pick the time step to be quite small in order for the scheme to be stable. Therefore, there are a lot of time steps during which "nothing interesting happens" in the solution. To improve overall efficiency – in particular, speed up the program and save disk space – we only output the solution every output_timestep_skip time steps:

main functionThis is the main function of the program. It creates an object of top-level class and calls its principal function. If exceptions are thrown during the execution of the run method of the SineGordonProblem class, we catch and report them here. For more information about exceptions the reader should consult step-6.

The explicit Euler time stepping scheme ( \theta=0) performs adequately for the problems we wish to solve. Unfortunately, a rather small time step has to be chosen due to stability issues — k\sim h/10 appears to work for most the simulations we performed. On the other hand, the Crank-Nicolson scheme ( \theta=\frac{1}{2}) is unconditionally stable, and (at least for the case of the 1D breather) we can pick the time step to be as large as 25h without any ill effects on the solution. The implicit Euler scheme ( \theta=1) is "exponentially damped," so it is not a good choice for solving the sine-Gordon equation, which is conservative. However, some of the damped schemes in the continuum that is offered by the \theta-method were useful for eliminating spurious oscillations due to boundary effects.

In the simulations below, we solve the sine-Gordon equation on the interval \Omega = [-10,10] in 1D and on the square \Omega = [-10,10]\times [-10,10] in 2D. In each case, the respective grid is refined uniformly 6 times, i.e. h\sim 2^{-6}.

The first example we discuss is the so-called 1D (stationary) breather solution of the sine-Gordon equation. The breather has the following closed-form expression, as mentioned in the Introduction:

u_{\mathrm{breather}}(x,t) = -4\arctan \left(\frac{m}{\sqrt{1-m^2}} \frac{\sin\left(\sqrt{1-m^2}t +c_2\right)}{\cosh(mx+c_1)} \right),

where c_1, c_2 and m<1 are constants. In the simulation below, we have chosen c_1=0, c_2=0, m=0.5. Moreover, it is know that the period of oscillation of the breather is 2\pi\sqrt{1-m^2}, hence we have chosen t_0=-5.4414 and t_f=2.7207 so that we can observe three oscillations of the solution. Then, taking u_0(x) = u_{\mathrm{breather}}(x,t_0), \theta=0 and k=h/10, the program computed the following solution.

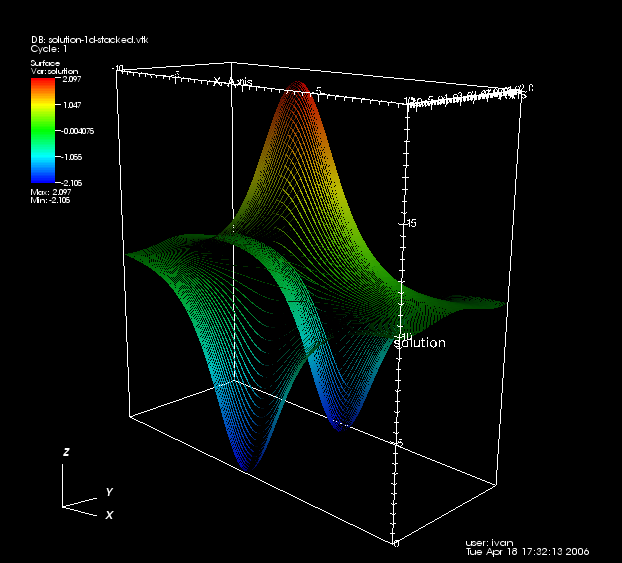

Though not shown how to do this in the program, another way to visualize the (1+1)-d solution is to use output generated by the DataOutStack class; it allows to "stack" the solutions of individual time steps, so that we get 2D space-time graphs from 1D time-dependent solutions. This produces the space-time plot below instead of the animation above.

Furthermore, since the breather is an analytical solution of the sine-Gordon equation, we can use it to validate our code, although we have to assume that the error introduced by our choice of Neumann boundary conditions is small compared to the numerical error. Under this assumption, one could use the VectorTools::integrate_difference function to compute the difference between the numerical solution and the function described by the ExactSolution class of this program. For the simulation shown in the two images above, the L^2 norm of the error in the finite element solution at each time step remained on the order of 10^{-2}. Hence, we can conclude that the numerical method has been implemented correctly in the program.

The only analytical solution to the sine-Gordon equation in (2+1)D that can be found in the literature is the so-called kink solitary wave. It has the following closed-form expression:

u(x,y,t) = 4 \arctan \left[a_0 e^{s\xi}\right]

with

\xi = x \cos\vartheta + \sin(\vartheta) (y\cosh\lambda + t\sinh \lambda)

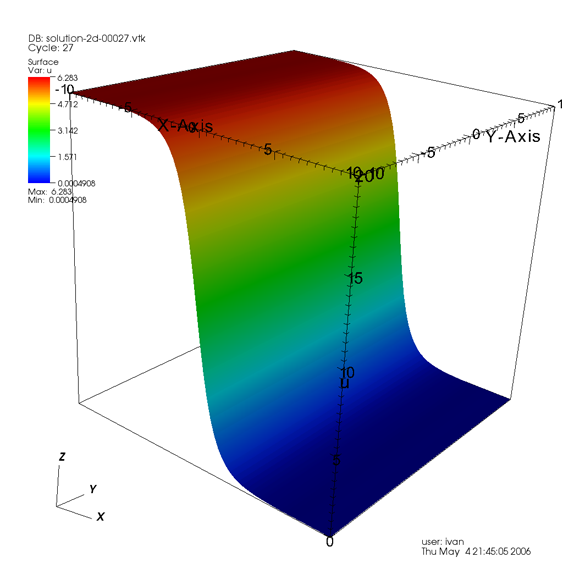

where a_0, \vartheta and \lambda are constants. In the simulation below we have chosen a_0=\lambda=1. Notice that if \vartheta=\pi the kink is stationary, hence it would make a good solution against which we can validate the program in 2D because no reflections off the boundary of the domain occur.

The simulation shown below was performed with u_0(x) = u_{\mathrm{kink}}(x,t_0), \theta=\frac{1}{2}, k=20h, t_0=1 and t_f=500. The L^2 norm of the error of the finite element solution at each time step remained on the order of 10^{-2}, showing that the program is working correctly in 2D, as well as 1D. Unfortunately, the solution is not very interesting, nonetheless we have included a snapshot of it below for completeness.

Now that we have validated the code in 1D and 2D, we move to a problem where the analytical solution is unknown.

To this end, we rotate the kink solution discussed above about the z axis: we let \vartheta=\frac{\pi}{4}. The latter results in a solitary wave that is not aligned with the grid, so reflections occur at the boundaries of the domain immediately. For the simulation shown below, we have taken u_0(x)=u_{\mathrm{kink}}(x,t_0), \theta=\frac{2}{3}, k=20h, t_0=0 and t_f=20. Moreover, we had to pick \theta=\frac{2}{3} because for any \theta\le\frac{1}{2} oscillations arose at the boundary, which are likely due to the scheme and not the equation, thus picking a value of \theta a good bit into the "exponentially damped" spectrum of the time stepping schemes assures these oscillations are not created.

Another interesting solution to the sine-Gordon equation (which cannot be obtained analytically) can be produced by using two 1D breathers to construct the following separable 2D initial condition:

u_0(x) = u_{\mathrm{pseudobreather}}(x,t_0) = 16\arctan \left( \frac{m}{\sqrt{1-m^2}} \frac{\sin\left(\sqrt{1-m^2}t_0\right)}{\cosh(mx_1)} \right) \arctan \left( \frac{m}{\sqrt{1-m^2}} \frac{\sin\left(\sqrt{1-m^2}t_0\right)}{\cosh(mx_2)} \right),

where x=(x_1,x_2)\in{R}^2, m=0.5<1 as in the 1D case we discussed above. For the simulation shown below, we have chosen \theta=\frac{1}{2}, k=10h, t_0=-5.4414 and t_f=2.7207. The solution is pretty interesting — it acts like a breather (as far as the pictures are concerned); however, it appears to break up and reassemble, rather than just oscillate.

It is instructive to change the initial conditions. Most choices will not lead to solutions that stay localized (in the soliton community, such solutions are called "stationary", though the solution does change with time), but lead to solutions where the wave-like character of the equation dominates and a wave travels away from the location of a localized initial condition. For example, it is worth playing around with the InitialValues class, by replacing the call to the ExactSolution class by something like this function:

u_0(x,y) = \cos\left(\frac x2\right)\cos\left(\frac y2\right)

if |x|,|y|\le \frac\pi 2, and u_0(x,y)=0 outside this region.

A second area would be to investigate whether the scheme is energy-preserving. For the pure wave equation, discussed in step-23, this is the case if we choose the time stepping parameter such that we get the Crank-Nicolson scheme. One could do a similar thing here, noting that the energy in the sine-Gordon solution is defined as

E(t) = \frac 12 \int_\Omega \left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial t}\right)^2 + \left(\nabla u\right)^2 + 2 (1-\cos u) \; dx.

(We use 1-\cos u instead of -\cos u in the formula to ensure that all contributions to the energy are positive, and so that decaying solutions have finite energy on unbounded domains.)

Beyond this, there are two obvious areas: