|

Reference documentation for deal.II version 9.3.3

|

|

Reference documentation for deal.II version 9.3.3

|

This tutorial depends on step-26, step-29.

This program was contributed by Wolfgang Bangerth (Colorado State University) and Yong-Yong Cai (Beijing Computational Science Research Center, CSRC) and is the result of the first author's time as a visitor at CSRC.

This material is based upon work partially supported by National Science Foundation grants OCI-1148116, OAC-1835673, DMS-1821210, and EAR-1925595; and by the Computational Infrastructure in Geodynamics initiative (CIG), through the National Science Foundation under Award No. EAR-1550901 and The University of California-Davis.

The Nonlinear Schrödinger Equation (NLSE) for a function \psi=\psi(\mathbf x,t) and a potential V=V(\mathbf x) is a model often used in quantum mechanics and nonlinear optics. If one measures in appropriate quantities (so that \hbar=1), then it reads as follows:

\begin{align*} - i \frac{\partial \psi}{\partial t} - \frac 12 \Delta \psi + V \psi + \kappa |\psi|^2 \psi &= 0 \qquad\qquad & \text{in}\; \Omega\times (0,T), \\ \psi(\mathbf x,0) &= \psi_0(\mathbf x) & \text{in}\; \Omega, \\ \psi(\mathbf x,t) &= 0 & \text{on}\; \partial\Omega\times (0,T). \end{align*}

If there is no potential, i.e. V(\mathbf x)=0, then it can be used to describe the propagation of light in optical fibers. If V(\mathbf x)\neq 0, the equation is also sometimes called the Gross-Pitaevskii equation and can be used to model the time dependent behavior of Bose-Einstein condensates.

For this particular tutorial program, the physical interpretation of the equation is not of much concern to us. Rather, we want to use it as a model that allows us to explain two aspects:

At first glance, the equations appear to be parabolic and similar to the heat equation (see step-26) as there is only a single time derivative and two spatial derivatives. But this is misleading. Indeed, that this is not the correct interpretation is more easily seen if we assume for a moment that the potential V=0 and \kappa=0. Then we have the equation

\begin{align*} - i \frac{\partial \psi}{\partial t} - \frac 12 \Delta \psi &= 0. \end{align*}

If we separate the solution into real and imaginary parts, \psi=v+iw, with v=\textrm{Re}\;\psi,\; w=\textrm{Im}\;\psi, then we can split the one equation into its real and imaginary parts in the same way as we did in step-29:

\begin{align*} \frac{\partial w}{\partial t} - \frac 12 \Delta v &= 0, \\ -\frac{\partial v}{\partial t} - \frac 12 \Delta w &= 0. \end{align*}

Not surprisingly, the factor i in front of the time derivative couples the real and imaginary parts of the equation. If we want to understand this equation further, take the time derivative of one of the equations, say

\begin{align*} \frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial t^2} - \frac 12 \Delta \frac{\partial v}{\partial t} &= 0, \end{align*}

(where we have assumed that, at least in some formal sense, we can commute the spatial and temporal derivatives), and then insert the other equation into it:

\begin{align*} \frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial t^2} + \frac 14 \Delta^2 w &= 0. \end{align*}

This equation is hyperbolic and similar in character to the wave equation. (This will also be obvious if you look at the video in the "Results" section of this program.) Furthermore, we could have arrived at the same equation for v as well. Consequently, a better assumption for the NLSE is to think of it as a hyperbolic, wave-propagation equation than as a diffusion equation such as the heat equation. (You may wonder whether it is correct that the operator \Delta^2 appears with a positive sign whereas in the wave equation, \Delta has a negative sign. This is indeed correct: After multiplying by a test function and integrating by parts, we want to come out with a positive (semi-)definite form. So, from -\Delta u we obtain +(\nabla v,\nabla u). Likewise, after integrating by parts twice, we obtain from +\Delta^2 u the form +(\Delta v,\Delta u). In both cases do we get the desired positive sign.)

The real NLSE, of course, also has the terms V\psi and \kappa|\psi|^2\psi. However, these are of lower order in the spatial derivatives, and while they are obviously important, they do not change the character of the equation.

In any case, the purpose of this discussion is to figure out what time stepping scheme might be appropriate for the equation. The conclusions is that, as a hyperbolic-kind of equation, we need to choose a time step that satisfies a CFL-type condition. If we were to use an explicit method (which we will not), we would have to investigate the eigenvalues of the matrix that corresponds to the spatial operator. If you followed the discussions of the video lectures (See also video lecture 26, video lecture 27, video lecture 28.) then you will remember that the pattern is that one needs to make sure that k^s \propto h^t where k is the time step, h the mesh width, and s,t are the orders of temporal and spatial derivatives. Whether you take the original equation ( s=1,t=2) or the reformulation for only the real or imaginary part, the outcome is that we would need to choose k \propto h^2 if we were to use an explicit time stepping method. This is not feasible for the same reasons as in step-26 for the heat equation: It would yield impractically small time steps for even only modestly refined meshes. Rather, we have to use an implicit time stepping method and can then choose a more balanced k \propto h. Indeed, we will use the implicit Crank-Nicolson method as we have already done in step-23 before for the regular wave equation.

If one thought of the NLSE as an ordinary differential equation in which the right hand side happens to have spatial derivatives, i.e., write it as

\begin{align*} \frac{d\psi}{dt} &= i\frac 12 \Delta \psi -i V \psi -i\kappa |\psi|^2 \psi, \qquad\qquad & \text{for}\; t \in (0,T), \\ \psi(0) &= \psi_0, \end{align*}

one may be tempted to "formally solve" it by integrating both sides over a time interval [t_{n},t_{n+1}] and obtain

\begin{align*} \psi(t_{n+1}) &= \psi(t_n) + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( i\frac 12 \Delta \psi(t) -i V \psi(t) -i\kappa |\psi(t)|^2 \psi(t) \right) \; dt. \end{align*}

Of course, it's not that simple: the \psi(t) in the integrand is still changing over time in accordance with the differential equation, so we cannot just evaluate the integral (or approximate it easily via quadrature) because we don't know \psi(t). But we can write this with separate contributions as follows, and this will allow us to deal with different terms separately:

\begin{align*} \psi(t_{n+1}) &= \psi(t_n) + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( i\frac 12 \Delta \psi(t) \right) \; dt + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( -i V \psi(t) \right) \; dt + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( -i\kappa |\psi(t)|^2 \,\psi(t) \right) \; dt. \end{align*}

The way this equation can now be read is as follows: For each time interval [t_{n},t_{n+1}], the change \psi(t_{n+1})-\psi(t_{n}) in the solution consists of three contributions:

Operator splitting is now an approximation technique that allows us to treat each of these contributions separately. (If we want: In practice, we will treat the first two together, and the last one separate. But that is a detail, conceptually we could treat all of them differently.) To this end, let us introduce three separate "solutions":

\begin{align*} \psi^{(1)}(t_{n+1}) &= \psi(t_n) + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( i\frac 12 \Delta \psi^{(1)}(t) \right) \; dt, \\ \psi^{(2)}(t_{n+1}) &= \psi(t_n) + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( -i V \psi^{(2)}(t) \right) \; dt, \\ \psi^{(3)}(t_{n+1}) &= \psi(t_n) + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( -i\kappa |\psi^{(3)}(t)|^2 \,\psi^{(3)}(t) \right) \; dt. \end{align*}

These three "solutions" can be thought of as satisfying the following differential equations:

\begin{align*} \frac{d\psi^{(1)}}{dt} &= i\frac 12 \Delta \psi^{(1)}, \qquad & \text{for}\; t \in (t_n,t_{n+1}), \qquad\qquad\text{with initial condition}\; \psi^{(1)}(t_n) &= \psi(t_n), \\ \frac{d\psi^{(2)}}{dt} &= -i V \psi^{(2)}, & \text{for}\; t \in (t_n,t_{n+1}), \qquad\qquad\text{with initial condition}\; \psi^{(2)}(t_n) &= \psi(t_n), \\ \frac{d\psi^{(3)}}{dt} &= -i\kappa |\psi^{(3)}|^2 \,\psi^{(3)}, & \text{for}\; t \in (t_n,t_{n+1}), \qquad\qquad\text{with initial condition}\; \psi^{(3)}(t_n) &= \psi(t_n). \end{align*}

In other words, they are all trajectories \psi^{(k)} that start at \psi(t_n) and integrate up the effects of exactly one of the three terms. The increments resulting from each of these terms over our time interval are then I^{(1)}=\psi^{(1)}(t_{n+1})-\psi(t_n), I^{(2)}=\psi^{(2)}(t_{n+1})-\psi(t_n), and I^{(3)}=\psi^{(3)}(t_{n+1})-\psi(t_n).

It is now reasonable to assume (this is an approximation!) that the change due to all three of the effects in question is well approximated by the sum of the three separate increments:

\begin{align*} \psi(t_{n+1})-\psi(t_n) \approx I^{(1)} + I^{(2)} + I^{(3)}. \end{align*}

This intuition is indeed correct, though the approximation is not exact: the difference between the exact left hand side and the term I^{(1)}+I^{(2)}+I^{(3)} (i.e., the difference between the exact increment for the exact solution \psi(t) when moving from t_n to t_{n+1}, and the increment composed of the three parts on the right hand side), is proportional to \Delta t=t_{n+1}-t_{n}. In other words, this approach introduces an error of size {\cal O}(\Delta t). Nothing we have done so far has discretized anything in time or space, so the overall error is going to be {\cal O}(\Delta t) plus whatever error we commit when approximating the integrals (the temporal discretization error) plus whatever error we commit when approximating the spatial dependencies of \psi (the spatial error).

Before we continue with discussions about operator splitting, let us talk about why one would even want to go this way? The answer is simple: For some of the separate equations for the \psi^{(k)}, we may have ways to solve them more efficiently than if we throw everything together and try to solve it at once. For example, and particularly pertinent in the current case: The equation for \psi^{(3)}, i.e.,

\begin{align*} \frac{d\psi^{(3)}}{dt} &= -i\kappa |\psi^{(3)}|^2 \,\psi^{(3)}, \qquad\qquad & \text{for}\; t \in (t_n,t_{n+1}), \qquad\qquad\text{with initial condition}\; \psi^{(3)}(t_n) &= \psi(t_n), \end{align*}

or equivalently,

\begin{align*} \psi^{(3)}(t_{n+1}) &= \psi(t_n) + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( -i\kappa |\psi^{(3)}(t)|^2 \,\psi^{(3)}(t) \right) \; dt, \end{align*}

can be solved exactly: the equation is solved by

\begin{align*} \psi^{(3)}(t) = e^{-i\kappa|\psi(t_n)|^2 (t-t_{n})} \psi(t_n). \end{align*}

This is easy to see if (i) you plug this solution into the differential equation, and (ii) realize that the magnitude |\psi^{(3)}| is constant, i.e., the term |\psi(t_n)|^2 in the exponent is in fact equal to |\psi^{(3)}(t)|^2. In other words, the solution of the ODE for \psi^{(3)}(t) only changes its phase, but the magnitude of the complex-valued function \psi^{(3)}(t) remains constant. This makes computing I^{(3)} particularly convenient: we don't actually need to solve any ODE, we can write the solution down by hand. Using the operator splitting approach, none of the methods to compute I^{(1)},I^{(2)} therefore have to deal with the nonlinear term and all of the associated unpleasantries: we can get away with solving only linear problems, as long as we allow ourselves the luxury of using an operator splitting approach.

Secondly, one often uses operator splitting if the different physical effects described by the different terms have different time scales. Imagine, for example, a case where we really did have some sort of diffusion equation. Diffusion acts slowly, but if \kappa is large, then the "phase rotation" by the term -i\kappa |\psi^{(3)}(t)|^2 \,\psi^{(3)}(t) acts quickly. If we treated everything together, this would imply having to take rather small time steps. But with operator splitting, we can take large time steps \Delta t=t_{n+1}-t_{n} for the diffusion, and (assuming we didn't have an analytic solution) use an ODE solver with many small time steps to integrate the "phase rotation" equation for \psi^{(3)} from t_n to t_{n+1}. In other words, operator splitting allows us to decouple slow and fast time scales and treat them differently, with methods adjusted to each case.

While the method above allows to compute the three contributions I^{(k)} in parallel, if we want, the method can be made slightly more accurate and easy to implement if we don't let the trajectories for the \psi^{(k)} start all at \psi(t_n), but instead let the trajectory for \psi^{(2)} start at the end point of the trajectory for \psi^{(1)}, namely \psi^{(1)}(t_{n+1}); similarly, we will start the trajectory for \psi^{(3)} start at the end point of the trajectory for \psi^{(2)}, namely \psi^{(2)}(t_{n+1}). This method is then called "Lie splitting" and has the same order of error as the method above, i.e., the splitting error is {\cal O}(\Delta t).

This variation of operator splitting can be written as follows (carefully compare the initial conditions to the ones above):

\begin{align*} \frac{d\psi^{(1)}}{dt} &= i\frac 12 \Delta \psi^{(1)}, \qquad & \text{for}\; t \in (t_n,t_{n+1}), \qquad\qquad\text{with initial condition}\; \psi^{(1)}(t_n) &= \psi(t_n), \\ \frac{d\psi^{(2)}}{dt} &= -i V \psi^{(2)}, & \text{for}\; t \in (t_n,t_{n+1}), \qquad\qquad\text{with initial condition}\; \psi^{(2)}(t_n) &= \psi^{(1)}(t_{n+1}), \\ \frac{d\psi^{(3)}}{dt} &= -i\kappa |\psi^{(3)}|^2 \,\psi^{(3)}, & \text{for}\; t \in (t_n,t_{n+1}), \qquad\qquad\text{with initial condition}\; \psi^{(3)}(t_n) &= \psi^{(2)}(t_{n+1}). \end{align*}

(Obviously, while the formulas above imply that we should solve these problems in this particular order, it is equally valid to first solve for trajectory 3, then 2, then 1, or any other permutation.)

The integrated forms of these equations are then

\begin{align*} \psi^{(1)}(t_{n+1}) &= \psi(t_n) + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( i\frac 12 \Delta \psi^{(1)}(t) \right) \; dt, \\ \psi^{(2)}(t_{n+1}) &= \psi^{(1)}(t_{n+1}) + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( -i V \psi^{(2)}(t) \right) \; dt, \\ \psi^{(3)}(t_{n+1}) &= \psi^{(2)}(t_{n+1}) + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( -i\kappa |\psi^{(3)}(t)|^2 \,\psi^{(3)}(t) \right) \; dt. \end{align*}

From a practical perspective, this has the advantage that we need to keep around fewer solution vectors: Once \psi^{(1)}(t_n) has been computed, we don't need \psi(t_n) any more; once \psi^{(2)}(t_n) has been computed, we don't need \psi^{(1)}(t_n) any more. And once \psi^{(3)}(t_n) has been computed, we can just call it \psi(t_{n+1}) because, if you insert the first into the second, and then into the third equation, you see that the right hand side of \psi^{(3)}(t_n) now contains the contributions of all three physical effects:

\begin{align*} \psi^{(3)}(t_{n+1}) &= \psi(t_n) + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( i\frac 12 \Delta \psi^{(1)}(t) \right) \; dt + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( -i V \psi^{(2)}(t) \right) \; dt+ \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( -i\kappa |\psi^{(3)}(t)|^2 \,\psi^{(3)}(t) \right) \; dt. \end{align*}

(Compare this again with the "exact" computation of \psi(t_{n+1}): It only differs in how we approximate \psi(t) in each of the three integrals.) In other words, Lie splitting is a lot simpler to implement that the original method outlined above because data handling is so much simpler.

As mentioned above, Lie splitting is only {\cal O}(\Delta t) accurate. This is acceptable if we were to use a first order time discretization, for example using the explicit or implicit Euler methods to solve the differential equations for \psi^{(k)}. This is because these time integration methods introduce an error proportional to \Delta t themselves, and so the splitting error is proportional to an error that we would introduce anyway, and does not diminish the overall convergence order.

But we typically want to use something higher order – say, a Crank-Nicolson or BDF2 method – since these are often not more expensive than a simple Euler method. It would be a shame if we were to use a time stepping method that is {\cal O}(\Delta t^2), but then lose the accuracy again through the operator splitting.

This is where the Strang splitting method comes in. It is easier to explain if we had only two parts, and so let us combine the effects of the Laplace operator and of the potential into one, and the phase rotation into a second effect. (Indeed, this is what we will do in the code since solving the equation with the Laplace equation with or without the potential costs the same – so we merge these two steps.) The Lie splitting method from above would then do the following: It computes solutions of the following two ODEs,

\begin{align*} \frac{d\psi^{(1)}}{dt} &= i\frac 12 \Delta \psi^{(1)} -i V \psi^{(1)}, \qquad & \text{for}\; t \in (t_n,t_{n+1}), \qquad\qquad\text{with initial condition}\; \psi^{(1)}(t_n) &= \psi(t_n), \\ \frac{d\psi^{(2)}}{dt} &= -i\kappa |\psi^{(2)}|^2 \,\psi^{(2)}, & \text{for}\; t \in (t_n,t_{n+1}), \qquad\qquad\text{with initial condition}\; \psi^{(2)}(t_n) &= \psi^{(1)}(t_{n+1}), \end{align*}

and then uses the approximation \psi(t_{n+1}) \approx \psi^{(2)}(t_{n+1}). In other words, we first make one full time step for physical effect one, then one full time step for physical effect two. The solution at the end of the time step is simply the sum of the increments due to each of these physical effects separately.

In contrast, Gil Strang (one of the titans of numerical analysis starting in the mid-20th century) figured out that it is more accurate to first do one half-step for one physical effect, then a full time step for the other physical effect, and then another half step for the first. Which one is which does not matter, but because it is so simple to do the phase rotation, we will use this effect for the half steps and then only need to do one spatial solve with the Laplace operator plus potential. This operator splitting method is now {\cal O}(\Delta t^2) accurate. Written in formulas, this yields the following sequence of steps:

\begin{align*} \frac{d\psi^{(1)}}{dt} &= -i\kappa |\psi^{(1)}|^2 \,\psi^{(1)}, && \text{for}\; t \in (t_n,t_n+\tfrac 12\Delta t), \qquad\qquad&\text{with initial condition}\; \psi^{(1)}(t_n) &= \psi(t_n), \\ \frac{d\psi^{(2)}}{dt} &= i\frac 12 \Delta \psi^{(2)} -i V \psi^{(2)}, \qquad && \text{for}\; t \in (t_n,t_{n+1}), \qquad\qquad&\text{with initial condition}\; \psi^{(2)}(t_n) &= \psi^{(1)}(t_n+\tfrac 12\Delta t), \\ \frac{d\psi^{(3)}}{dt} &= -i\kappa |\psi^{(3)}|^2 \,\psi^{(3)}, && \text{for}\; t \in (t_n+\tfrac 12\Delta t,t_{n+1}), \qquad\qquad&\text{with initial condition}\; \psi^{(3)}(t_n) &= \psi^{(2)}(t_{n+1}). \end{align*}

As before, the first and third step can be computed exactly for this particular equation, yielding

\begin{align*} \psi^{(1)}(t_n+\tfrac 12\Delta t) &= e^{-i\kappa|\psi(t_n)|^2 \tfrac 12\Delta t} \; \psi(t_n), \\ \psi^{(3)}(t_{n+1}) &= e^{-i\kappa|\psi^{(2)}(t_{n+1})|^2 \tfrac 12\Delta t} \; \psi^{(2)}(t_{n+1}). \end{align*}

This is then how we are going to implement things in this program: In each time step, we execute three steps, namely

This structure will be reflected in an obvious way in the main time loop of the program.

From the discussion above, it should have become clear that the only partial differential equation we have to solve in each time step is

\begin{align*} -i\frac{\partial\psi^{(2)}}{\partial t} - \frac 12 \Delta \psi^{(2)} + V \psi^{(2)} = 0. \end{align*}

This equation is linear. Furthermore, we only have to solve it from t_n to t_{n+1}, i.e., for exactly one time step.

To do this, we will apply the second order accurate Crank-Nicolson scheme that we have already used in some of the other time dependent codes (specifically: step-23 and step-26). It reads as follows:

\begin{align*} -i\frac{\psi^{(n,2)}-\psi^{(n,1)}}{k_{n+1}} - \frac 12 \Delta \left[\frac 12 \left(\psi^{(n,2)}+\psi^{(n,1)}\right)\right] + V \left[\frac 12 \left(\psi^{(n,2)}+\psi^{(n,1)}\right)\right] = 0. \end{align*}

Here, the "previous" solution \psi^{(n,1)} (or the "initial condition" for this part of the time step) is the output of the first phase rotation half-step; the output of the current step will be denoted by \psi^{(n,2)}. k_{n+1}=t_{n+1}-t_n is the length of the time step. (One could argue whether \psi^{(n,1)} and \psi^{(n,1)} live at time step n or n+1 and what their upper indices should be. This is a philosophical discussion without practical impact, and one might think of \psi^{(n,1)} as something like \psi^{(n+\tfrac 13)}, and \psi^{(n,2)} as \psi^{(n+\tfrac 23)} if that helps clarify things – though, again n+\frac 13 is not to be understood as "one third time step after \_form#398" but more like "we've already done one third of the work necessary for time step \_form#2716".)

If we multiply the whole equation with k_{n+1} and sort terms with the unknown \psi^{(n+1,2)} to the left and those with the known \psi^{(n,2)} to the right, then we obtain the following (spatial) partial differential equation that needs to be solved in each time step:

\begin{align*} -i\psi^{(n,2)} - \frac 14 k_{n+1} \Delta \psi^{(n,2)} + \frac 12 k_{n+1} V \psi^{(n,2)} = -i\psi^{(n,1)} + \frac 14 k_{n+1} \Delta \psi^{(n,1)} - \frac 12 k_{n+1} V \psi^{(n,1)}. \end{align*}

As mentioned above, the previous tutorial program dealing with complex-valued solutions (namely, step-29) separated real and imaginary parts of the solution. It thus reduced everything to real arithmetic. In contrast, we here want to keep things complex-valued.

The first part of this is that we need to define the discretized solution as \psi_h^n(\mathbf x)=\sum_j \Psi^n_j \varphi_j(\mathbf x) \approx \psi(\mathbf x,t_n) where the \varphi_j are the usual shape functions (which are real valued) but the expansion coefficients \Psi^n_j at time step n are now complex-valued. This is easily done in deal.II: We just have to use Vector<std::complex<double>> instead of Vector<double> to store these coefficients.

Of more interest is how to build and solve the linear system. Obviously, this will only be necessary for the second step of the Strang splitting discussed above, with the time discretization of the previous subsection. We obtain the fully discrete version through straightforward substitution of \psi^n by \psi^n_h and multiplication by a test function:

\begin{align*} -iM\Psi^{(n,2)} + \frac 14 k_{n+1} A \Psi^{(n,2)} + \frac 12 k_{n+1} W \Psi^{(n,2)} = -iM\Psi^{(n+1,1)} - \frac 14 k_{n+1} A \Psi^{(n,1)} - \frac 12 k_{n+1} W \Psi^{(n,1)}, \end{align*}

or written in a more compact way:

\begin{align*} \left[ -iM + \frac 14 k_{n+1} A + \frac 12 k_{n+1} W \right] \Psi^{(n,2)} = \left[ -iM - \frac 14 k_{n+1} A - \frac 12 k_{n+1} W \right] \Psi^{(n,1)}. \end{align*}

Here, the matrices are defined in their obvious ways:

\begin{align*} M_{ij} &= (\varphi_i,\varphi_j), \\ A_{ij} &= (\nabla\varphi_i,\nabla\varphi_j), \\ W_{ij} &= (\varphi_i,V \varphi_j). \end{align*}

Note that all matrices individually are in fact symmetric, real-valued, and at least positive semidefinite, though the same is obviously not true for the system matrix C = -iM + \frac 14 k_{n+1} A + \frac 12 k_{n+1} W and the corresponding matrix R = -iM - \frac 14 k_{n+1} A - \frac 12 k_{n+1} W on the right hand side.

The only remaining important question about the solution procedure is how to solve the complex-valued linear system

\begin{align*} C \Psi^{(n+1,2)} = R \Psi^{(n+1,1)}, \end{align*}

with the matrix C = -iM + \frac 14 k_{n+1} A + \frac 12 k_{n+1} W and a right hand side that is easily computed as the product of a known matrix and the previous part-step's solution. As usual, this comes down to the question of what properties the matrix C has. If it is symmetric and positive definite, then we can for example use the Conjugate Gradient method.

Unfortunately, the matrix's only useful property is that it is complex symmetric, i.e., C_{ij}=C_{ji}, as is easy to see by recalling that M,A,W are all symmetric. It is not, however, Hermitian, which would require that C_{ij}=\bar C_{ji} where the bar indicates complex conjugation.

Complex symmetry can be exploited for iterative solvers as a quick literature search indicates. We will here not try to become too sophisticated (and indeed leave this to the Possibilities for extensions section below) and instead simply go with the good old standby for problems without properties: A direct solver. That's not optimal, especially for large problems, but it shall suffice for the purposes of a tutorial program. Fortunately, the SparseDirectUMFPACK class allows solving complex-valued problems.

Initial conditions for the NLSE are typically chosen to represent particular physical situations. This is beyond the scope of this program, but suffice it to say that these initial conditions are (i) often superpositions of the wave functions of particles located at different points, and that (ii) because |\psi(\mathbf x,t)|^2 corresponds to a particle density function, the integral

N(t) = \int_\Omega |\psi(\mathbf x,t)|^2

corresponds to the number of particles in the system. (Clearly, if one were to be physically correct, N(t) better be a constant if the system is closed, or \frac{dN}{dt}<0 if one has absorbing boundary conditions.) The important point is that one should choose initial conditions so that

N(0) = \int_\Omega |\psi_0(\mathbf x)|^2

makes sense.

What we will use here, primarily because it makes for good graphics, is the following:

\psi_0(\mathbf x) = \sqrt{\sum_{k=1}^4 \alpha_k e^{-\frac{r_k^2}{R^2}}},

where r_k = |\mathbf x-\mathbf x_k| is the distance from the (fixed) locations \mathbf x_k, and \alpha_k are chosen so that each of the Gaussians that we are adding up adds an integer number of particles to N(0). We achieve this by making sure that

\int_\Omega \alpha_k e^{-\frac{r_k^2}{R^2}}

is a positive integer. In other words, we need to choose \alpha as an integer multiple of

\left(\int_\Omega e^{-\frac{r_k^2}{R^2}}\right)^{-1} = \left(R^d\sqrt{\pi^d}\right)^{-1},

assuming for the moment that \Omega={\mathbb R}^d – which is of course not the case, but we'll ignore the small difference in integral.

Thus, we choose \alpha_k=\left(R^d\sqrt{\pi^d}\right)^{-1} for all, and R=0.1. This R is small enough that the difference between the exact (infinite) integral and the integral over \Omega should not be too concerning. We choose the four points \mathbf x_k as (\pm 0.3, 0), (0, \pm 0.3) – also far enough away from the boundary of \Omega to keep ourselves on the safe side.

For simplicity, we pose the problem on the square [-1,1]^2. For boundary conditions, we will use time-independent Neumann conditions of the form

\nabla\psi(\mathbf x,t)\cdot \mathbf n=0 \qquad\qquad \forall \mathbf x\in\partial\Omega.

This is not a realistic choice of boundary conditions but sufficient for what we want to demonstrate here. We will comment further on this in the Possibilities for extensions section below.

Finally, we choose \kappa=1, and the potential as

V(\mathbf x) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if}\; |\mathbf x|<0.7 \\ 1000 & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases}

Using a large potential makes sure that the wave function \psi remains small outside the circle of radius 0.7. All of the Gaussians that make up the initial conditions are within this circle, and the solution will mostly oscillate within it, with a small amount of energy radiating into the outside. The use of a large potential also makes sure that the nonphysical boundary condition does not have too large an effect.

The program starts with the usual include files, all of which you should have seen before by now:

Then the usual placing of all content of this program into a namespace and the importation of the deal.II namespace into the one we will work in:

NonlinearSchroedingerEquation classThen the main class. It looks very much like the corresponding classes in step-4 or step-6, with the only exception that the matrices and vectors and everything else related to the linear system are now storing elements of type std::complex<double> instead of just double.

Before we go on filling in the details of the main class, let us define the equation data corresponding to the problem, i.e. initial values, as well as a right hand side class. (We will reuse the initial conditions also for the boundary values, which we simply keep constant.) We do so using classes derived from the Function class template that has been used many times before, so the following should not look surprising. The only point of interest is that we here have a complex-valued problem, so we have to provide the second template argument of the Function class (which would otherwise default to double). Furthermore, the return type of the value() functions is then of course also complex.

What precisely these functions return has been discussed at the end of the Introduction section.

NonlinearSchroedingerEquation classWe start by specifying the implementation of the constructor of the class. There is nothing of surprise to see here except perhaps that we choose quadratic ( Q_2) Lagrange elements – the solution is expected to be smooth, so we choose a higher polynomial degree than the bare minimum.

The next function is the one that sets up the mesh, DoFHandler, and matrices and vectors at the beginning of the program, i.e. before the first time step. The first few lines are pretty much standard if you've read through the tutorial programs at least up to step-6:

Next, we assemble the relevant matrices. The way we have written the Crank-Nicolson discretization of the spatial step of the Strang splitting (i.e., the second of the three partial steps in each time step), we were led to the linear system \left[ -iM + \frac 14 k_{n+1} A + \frac 12 k_{n+1} W \right] \Psi^{(n,2)} = \left[ -iM - \frac 14 k_{n+1} A - \frac 12 k_{n+1} W \right] \Psi^{(n,1)}. In other words, there are two matrices in play here – one for the left and one for the right hand side. We build these matrices separately. (One could avoid building the right hand side matrix and instead just form the action of the matrix on \Psi^{(n,1)} in each time step. This may or may not be more efficient, but efficiency is not foremost on our minds for this program.)

Having set up all data structures above, we are now in a position to implement the partial steps that form the Strang splitting scheme. We start with the half-step to advance the phase, and that is used as the first and last part of each time step.

To this end, recall that for the first half step, we needed to compute \psi^{(n,1)} = e^{-i\kappa|\psi^{(n,0)}|^2 \tfrac 12\Delta t} \; \psi^{(n,0)}. Here, \psi^{(n,0)}=\psi^{(n)} and \psi^{(n,1)} are functions of space and correspond to the output of the previous complete time step and the result of the first of the three part steps, respectively. A corresponding solution must be computed for the third of the part steps, i.e. \psi^{(n,3)} = e^{-i\kappa|\psi^{(n,2)}|^2 \tfrac 12\Delta t} \; \psi^{(n,2)}, where \psi^{(n,3)}=\psi^{(n+1)} is the result of the time step as a whole, and its input \psi^{(n,2)} is the result of the spatial step of the Strang splitting.

An important realization is that while \psi^{(n,0)}(\mathbf x) may be a finite element function (i.e., is piecewise polynomial), this may not necessarily be the case for the "rotated" function in which we have updated the phase using the exponential factor (recall that the amplitude of that function remains constant as part of that step). In other words, we could compute \psi^{(n,1)}(\mathbf x) at every point \mathbf x\in\Omega, but we can't represent it on a mesh because it is not a piecewise polynomial function. The best we can do in a discrete setting is to compute a projection or interpolation. In other words, we can compute \psi_h^{(n,1)}(\mathbf x) = \Pi_h \left(e^{-i\kappa|\psi_h^{(n,0)}(\mathbf x)|^2 \tfrac 12\Delta t} \; \psi_h^{(n,0)}(\mathbf x) \right) where \Pi_h is a projection or interpolation operator. The situation is particularly simple if we choose the interpolation: Then, all we need to compute is the value of the right hand side at the node points and use these as nodal values for the vector \Psi^{(n,1)} of degrees of freedom. This is easily done because evaluating the right hand side at node points for a Lagrange finite element as used here requires us to only look at a single (complex-valued) entry of the node vector. In other words, what we need to do is to compute \Psi^{(n,1)}_j = e^{-i\kappa|\Psi^{(n,0)}_j|^2 \tfrac 12\Delta t} \; \Psi^{(n,0)}_j where j loops over all of the entries of our solution vector. This is what the function below does – in fact, it doesn't even use separate vectors for \Psi^{(n,0)} and \Psi^{(n,1)}, but just updates the same vector as appropriate.

The next step is to solve for the linear system in each time step, i.e., the second half step of the Strang splitting we use. Recall that it had the form C\Psi^{(n,2)} = R\Psi^{(n,1)} where C and R are the matrices we assembled earlier.

The way we solve this here is using a direct solver. We first form the right hand side r=R\Psi^{(n,1)} using the SparseMatrix::vmult() function and put the result into the system_rhs variable. We then call SparseDirectUMFPACK::solver() which takes as argument the matrix C and the right hand side vector and returns the solution in the same vector system_rhs. The final step is then to put the solution so computed back into the solution variable.

The last of the helper functions and classes we ought to discuss are the ones that create graphical output. The result of running the half and full steps for the local and spatial parts of the Strang splitting is that we have updated the solution vector \Psi^n to the correct value at the end of each time step. Its entries contain complex numbers for the solution at the nodes of the finite element mesh.

Complex numbers are not easily visualized. We can output their real and imaginary parts, i.e., the fields \text{Re}(\psi_h^{(n)}(\mathbf x)) and \text{Im}(\psi_h^{(n)}(\mathbf x)), and that is exactly what the DataOut class does when one attaches as complex-valued vector via DataOut::add_data_vector() and then calls DataOut::build_patches(). That is indeed what we do below.

But oftentimes we are not particularly interested in real and imaginary parts of the solution vector, but instead in derived quantities such as the magnitude |\psi| and phase angle \text{arg}(\psi) of the solution. In the context of quantum systems such as here, the magnitude itself is not so interesting, but instead it is the "amplitude", |\psi|^2 that is a physical property: it corresponds to the probability density of finding a particle in a particular place of state. The way to put computed quantities into output files for visualization – as used in numerous previous tutorial programs – is to use the facilities of the DataPostprocessor and derived classes. Specifically, both the amplitude of a complex number and its phase angles are scalar quantities, and so the DataPostprocessorScalar class is the right tool to base what we want to do on.

Consequently, what we do here is to implement two classes ComplexAmplitude and ComplexPhase that compute for each point at which DataOut decides to generate output, the amplitudes |\psi_h|^2 and phases \text{arg}(\psi_h) of the solution for visualization. There is a fair amount of boiler-plate code below, with the only interesting parts of the first of these two classes being how its evaluate_vector_field() function computes the computed_quantities object.

(There is also the rather awkward fact that the std::norm() function does not compute what one would naively imagine, namely |\psi|, but returns |\psi|^2 instead. It's certainly quite confusing to have a standard function mis-named in such a way...)

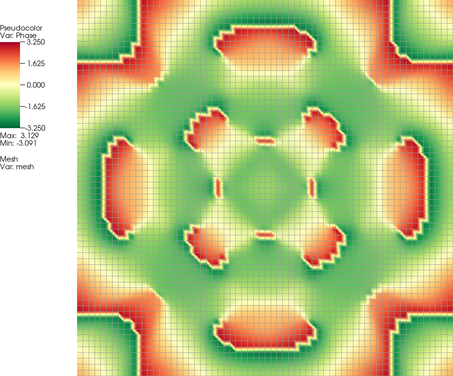

The second of these postprocessor classes computes the phase angle of the complex-valued solution at each point. In other words, if we represent \psi(\mathbf x,t)=r(\mathbf x,t) e^{i\varphi(\mathbf x,t)}, then this class computes \varphi(\mathbf x,t). The function std::arg does this for us, and returns the angle as a real number between -\pi and +\pi.

For reasons that we will explain in detail in the results section, we do not actually output this value at each location where output is generated. Rather, we take the maximum over all evaluation points of the phase and then fill each evaluation point's output field with this maximum – in essence, we output the phase angle as a piecewise constant field, where each cell has its own constant value. The reasons for this will become clear once you read through the discussion further down below.

Having so implemented these post-processors, we create output as we always do. As in many other time-dependent tutorial programs, we attach flags to DataOut that indicate the number of the time step and the current simulation time.

The remaining step is how we set up the overall logic for this program. It's really relatively simple: Set up the data structures; interpolate the initial conditions onto finite element space; then iterate over all time steps, and on each time step perform the three parts of the Strang splitting method. Every tenth time step, we generate graphical output. That's it.

The rest is again boiler plate and exactly as in almost all of the previous tutorial programs:

Running the code results in screen output like the following:

Running the program also yields a good number of output files that we will visualize in the following.

The output_results() function of this program generates output files that consist of a number of variables: The solution (split into its real and imaginary parts), the amplitude, and the phase. If we visualize these four fields, we get images like the following after a few time steps (at time t=0.242, to be precise:

While the real and imaginary parts of the solution shown above are not particularly interesting (because, from a physical perspective, the global offset of the phase and therefore the balance between real and imaginary components, is meaningless), it is much more interesting to visualize the amplitude |\psi(\mathbf x,t)|^2 and phase \text{arg}(\psi(\mathbf x,t)) of the solution and, in particular, their evolution. This leads to pictures like the following:

The phase picture shown here clearly has some flaws:

nic_Edge map in which both of the extreme values are shown as black.ComplexPhase class just uses the maximal phase angle encountered on each cell.With these modifications, the phase plot now looks as follows:

Finally, we can generate a movie out of this. (To be precise, the video uses two more global refinement cycles and a time step half the size of what is used in the program above.) The author of these lines made the movie with VisIt, because that's what he's more familiar with, and using a hacked color map that is also cyclic – though this color map lacks all of the skill employed by the people who wrote the posts mentioned in the links above. It does, however, show the character of the solution as a wave equation if you look at the shaded part of the domain outside the circle of radius 0.7 in which the potential is zero – you can see how every time one of the bumps (showing the amplitude |\psi_h(\mathbf x,t)|^2) bumps into the area where the potential is large: a wave travels outbound from there. Take a look at the video:

So why did I end up shading the area where the potential V(\mathbf x) is large? In that outside region, the solution is relatively small. It is also relatively smooth. As a consequence, to some approximate degree, the equation in that region simplifies to

- i \frac{\partial \psi}{\partial t} + V \psi \approx 0,

or maybe easier to read:

\frac{\partial \psi}{\partial t} \approx - i V \psi.

To the degree to which this approximation is valid (which, among other things, eliminates the traveling waves you can see in the video), this equation has a solution

\psi(\mathbf x, t) = \psi(\mathbf x, 0) e^{-i V t}.

Because V is large, this means that the phase rotates quite rapidly. If you focus on the semi-transparent outer part of the domain, you can see that. If one colors this region in the same way as the inner part of the domain, this rapidly flashing outer part may be psychedelic, but is also distracting of what's happening on the inside; it's also quite hard to actually see the radiating waves that are easy to see at the beginning of the video.

The solver chosen here is just too simple. It is also not efficient. What we do here is give the matrix to a sparse direct solver in every time step and let it find the solution of the linear system. But we know that we could do far better:

In order to be usable for actual, realistic problems, solvers for the nonlinear Schrödinger equation need to utilize boundary conditions that make sense for the problem at hand. We have here restricted ourselves to simple Neumann boundary conditions – but these do not actually make sense for the problem. Indeed, the equations are generally posed on an infinite domain. But, since we can't compute on infinite domains, we need to truncate it somewhere and instead pose boundary conditions that make sense for this artificially small domain. The approach widely used is to use the Perfectly Matched Layer method that corresponds to a particular kind of attenuation. It is, in a different context, also used in step-62.

Finally, we know from experience and many other tutorial programs that it is worthwhile to use adaptively refined meshes, rather than the uniform meshes used here. It would, in fact, not be very difficult to add this here: It just requires periodic remeshing and transfer of the solution from one mesh to the next. step-26 will be a good guide for how this could be implemented.