|

Reference documentation for deal.II version 9.1.1

|

|

Reference documentation for deal.II version 9.1.1

|

This tutorial depends on step-4.

| Table of contents | |

|---|---|

This program was contributed by Moritz Allmaras at Texas A&M University. Some of the work on this tutorial program has been funded by NSF under grant DMS-0604778.

Note: In order to run this program, deal.II must be configured to use the UMFPACK sparse direct solver. Refer to the ReadMe for instructions how to do this.

A question that comes up frequently is how to solve problems involving complex valued functions with deal.II. For many problems, instead of working with complex valued finite elements directly, which are not readily available in the library, it is often much more convenient to split complex valued functions into their real and imaginary parts and use separate scalar finite element fields for discretizing each one of them. Basically this amounts to viewing a single complex valued equation as a system of two real valued equations. This short example demonstrates how this can be implemented in deal.II by using an FE_system object to stack two finite element fields representing real and imaginary parts. We also revisit the ParameterHandler class first used in step-19, which provides a convenient way for reading parameters from a configuration file at runtime without the need to recompile the program code.

The equations covered here fall into the class of vector-valued problems. A top level overview of this topic can be found in the Handling vector valued problems module.

The original purpose of this program is to simulate the focusing properties of an ultrasound wave generated by a transducer lens with variable geometry. Recent applications in medical imaging use ultrasound waves not only for imaging purposes, but also to excite certain local effects in a material, like changes in optical properties, that can then be measured by other imaging techniques. A vital ingredient for these methods is the ability to focus the intensity of the ultrasound wave in a particular part of the material, ideally in a point, to be able to examine the properties of the material at that particular location.

To derive a model for this problem, we think of ultrasound as a pressure wave governed by the wave equation:

\[ \frac{\partial^2 U}{\partial t^2} - c^2 \Delta U = 0 \]

where \(c\) is the wave speed (that for simplicity we assume to be constant), \(U = U(x,t),\;x \in \Omega,\;t\in\mathrm{R}\). The boundary \(\Gamma=\partial\Omega\) is divided into two parts \(\Gamma_1\) and \(\Gamma_2=\Gamma\setminus\Gamma_1\), with \(\Gamma_1\) representing the transducer lens and \(\Gamma_2\) an absorbing boundary (that is, we want to choose boundary conditions on \(\Gamma_2\) in such a way that they imitate a larger domain). On \(\Gamma_1\), the transducer generates a wave of constant frequency \({\omega}>0\) and constant amplitude (that we chose to be 1 here):

\[ U(x,t) = \cos{\omega t}, \qquad x\in \Gamma_1 \]

If there are no other (interior or boundary) sources, and since the only source has frequency \(\omega\), then the solution admits a separation of variables of the form \(U(x,t) = \textrm{Re}\left(u(x)\,e^{i\omega t})\right)\). The complex-valued function \(u(x)\) describes the spatial dependency of amplitude and phase (relative to the source) of the waves of frequency \({\omega}\), with the amplitude being the quantity that we are interested in. By plugging this form of the solution into the wave equation, we see that for \(u\) we have

\begin{eqnarray*} -\omega^2 u(x) - c^2\Delta u(x) &=& 0, \qquad x\in\Omega,\\ u(x) &=& 1, \qquad x\in\Gamma_1. \end{eqnarray*}

For finding suitable conditions on \(\Gamma_2\) that model an absorbing boundary, consider a wave of the form \(V(x,t)=e^{i(k\cdot x -\omega t)}\) with frequency \({\omega}\) traveling in direction \(k\in {\mathrm{R}^2}\). In order for \(V\) to solve the wave equation, \(|k|={\frac{\omega}{c}}\) must hold. Suppose that this wave hits the boundary in \(x_0\in\Gamma_2\) at a right angle, i.e. \(n=\frac{k}{|k|}\) with \(n\) denoting the outer unit normal of \(\Omega\) in \(x_0\). Then at \(x_0\), this wave satisfies the equation

\[ c (n\cdot\nabla V) + \frac{\partial V}{\partial t} = (i\, c\, |k| - i\, \omega) V = 0. \]

Hence, by enforcing the boundary condition

\[ c (n\cdot\nabla U) + \frac{\partial U}{\partial t} = 0, \qquad x\in\Gamma_2, \]

waves that hit the boundary \(\Gamma_2\) at a right angle will be perfectly absorbed. On the other hand, those parts of the wave field that do not hit a boundary at a right angle do not satisfy this condition and enforcing it as a boundary condition will yield partial reflections, i.e. only parts of the wave will pass through the boundary as if it wasn't here whereas the remaining fraction of the wave will be reflected back into the domain.

If we are willing to accept this as a sufficient approximation to an absorbing boundary we finally arrive at the following problem for \(u\):

\begin{eqnarray*} -\omega^2 u - c^2\Delta u &=& 0, \qquad x\in\Omega,\\ c (n\cdot\nabla u) + i\,\omega\,u &=&0, \qquad x\in\Gamma_2,\\ u &=& 1, \qquad x\in\Gamma_1. \end{eqnarray*}

This is a Helmholtz equation (similar to the one in step-7, but this time with ''the bad sign'') with Dirichlet data on \(\Gamma_1\) and mixed boundary conditions on \(\Gamma_2\). Because of the condition on \(\Gamma_2\), we cannot just treat the equations for real and imaginary parts of \(u\) separately. What we can do however is to view the PDE for \(u\) as a system of two PDEs for the real and imaginary parts of \(u\), with the boundary condition on \(\Gamma_2\) representing the coupling terms between the two components of the system. This works along the following lines: Let \(v=\textrm{Re}\;u,\; w=\textrm{Im}\;u\), then in terms of \(v\) and \(w\) we have the following system:

\begin{eqnarray*} \left.\begin{array}{ccc} -\omega^2 v - c^2\Delta v &=& 0 \quad\\ -\omega^2 w - c^2\Delta w &=& 0 \quad \end{array}\right\} &\;& x\in\Omega, \\ \left.\begin{array}{ccc} c (n\cdot\nabla v) - \omega\,w &=& 0 \quad\\ c (n\cdot\nabla w) + \omega\,v &=& 0 \quad \end{array}\right\} &\;& x\in\Gamma_2, \\ \left.\begin{array}{ccc} v &=& 1 \quad\\ w &=& 0 \quad \end{array}\right\} &\;& x\in\Gamma_1. \end{eqnarray*}

For test functions \(\phi,\psi\) with \(\phi|_{\Gamma_1}=\psi|_{\Gamma_1}=0\), after the usual multiplication, integration over \(\Omega\) and applying integration by parts, we get the weak formulation

\begin{eqnarray*} -\omega^2 \langle \phi, v \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Omega)} + c^2 \langle \nabla \phi, \nabla v \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Omega)} - c \omega \langle \phi, w \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Gamma_2)} &=& 0, \\ -\omega^2 \langle \psi, w \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Omega)} + c^2 \langle \nabla \psi, \nabla w \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Omega)} + c \omega \langle \psi, v \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Gamma_2)} &=& 0. \end{eqnarray*}

We choose finite element spaces \(V_h\) and \(W_h\) with bases \(\{\phi_j\}_{j=1}^n, \{\psi_j\}_{j=1}^n\) and look for approximate solutions

\[ v_h = \sum_{j=1}^n \alpha_j \phi_j, \;\; w_h = \sum_{j=1}^n \beta_j \psi_j. \]

Plugging into the variational form yields the equation system

\[ \renewcommand{\arraystretch}{2.0} \left.\begin{array}{ccc} \sum_{j=1}^n \left( -\omega^2 \langle \phi_i, \phi_j \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Omega)} + c^2 \langle \nabla \phi_i, \nabla \phi_j \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Omega)} \right) \alpha_j - \left( c\omega \langle \phi_i,\psi_j\rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Gamma_2)}\right)\beta_j &=& 0 \\ \sum_{j=1}^n \left( -\omega^2 \langle \psi_i, \psi_j \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Omega)} + c^2 \langle \nabla \psi_i, \nabla \psi_j \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Omega)} \right)\beta_j + \left( c\omega \langle \psi_i,\phi_j\rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Gamma_2)} \right)\alpha_j &=& 0 \end{array}\right\}\;\;\forall\; i =1,\ldots,n. \]

In matrix notation:

\[ \renewcommand{\arraystretch}{2.0} \left( \begin{array}{cc} -\omega^2 \langle \phi_i, \phi_j \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Omega)} + c^2 \langle \nabla \phi_i, \nabla \phi_j \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Omega)} & -c\omega \langle \phi_i,\psi_j\rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Gamma_2)} \\ c\omega \langle \psi_i,\phi_j\rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Gamma_2)} & -\omega^2 \langle \psi_{i}, \psi_j \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Omega)} + c^2 \langle \nabla \psi_{i}, \nabla \psi_j \rangle_{\mathrm{L}^2(\Omega)} \end{array} \right) \left( \begin{array}{c} \alpha \\ \beta \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right) \]

(One should not be fooled by the right hand side being zero here, that is because we haven't included the Dirichlet boundary data yet.) Because of the alternating sign in the off-diagonal blocks, we can already see that this system is non-symmetric, in fact it is even indefinite. Of course, there is no necessity to choose the spaces \(V_h\) and \(W_h\) to be the same. However, we expect real and imaginary part of the solution to have similar properties and will therefore indeed take \(V_h=W_h\) in the implementation, and also use the same basis functions \(\phi_i = \psi_i\) for both spaces. The reason for the notation using different symbols is just that it allows us to distinguish between shape functions for \(v\) and \(w\), as this distinction plays an important role in the implementation.

For the computations, we will consider wave propagation in the unit square, with ultrasound generated by a transducer lens that is shaped like a segment of the circle with center at \((0.5, d)\) and a radius slightly greater than \(d\); this shape should lead to a focusing of the sound wave at the center of the circle. Varying \(d\) changes the "focus" of the lens and affects the spatial distribution of the intensity of \(u\), where our main concern is how well \(|u|=\sqrt{v^2+w^2}\) is focused.

In the program below, we will implement the complex-valued Helmholtz equations using the formulation with split real and imaginary parts. We will also discuss how to generate a domain that looks like a square with a slight bulge simulating the transducer (in the UltrasoundProblem<dim>::make_grid() function), and how to generate graphical output that not only contains the solution components \(v\) and \(w\), but also the magnitude \(\sqrt{v^2+w^2}\) directly in the output file (in UltrasoundProblem<dim>::output_results()). Finally, we use the ParameterHandler class to easily read parameters like the focal distance \(d\), wave speed \(c\), frequency \(\omega\), and a number of other parameters from an input file at run-time, rather than fixing those parameters in the source code where we would have to re-compile every time we want to change parameters.

The following header files have all been discussed before:

This header file contains the necessary declarations for the ParameterHandler class that we will use to read our parameters from a configuration file :

For solving the linear system, we'll use the sparse LU-decomposition provided by UMFPACK (see the SparseDirectUMFPACK class), for which the following header file is needed. Note that in order to compile this tutorial program, the deal.II-library needs to be built with UMFPACK support, which is enabled by default:

The FESystem class allows us to stack several FE-objects to one compound, vector-valued finite element field. The necessary declarations for this class are provided in this header file :

Finally, include the header file that declares the Timer class that we will use to determine how much time each of the operations of our program takes:

As the last step at the beginning of this program, we put everything that is in this program into its namespace and, within it, make everything that is in the deal.II namespace globally available, without the need to prefix everything with dealii:::

DirichletBoundaryValues classFirst we define a class for the function representing the Dirichlet boundary values. This has been done many times before and therefore does not need much explanation.

Since there are two values \(v\) and \(w\) that need to be prescribed at the boundary, we have to tell the base class that this is a vector-valued function with two components, and the vector_value function and its cousin vector_value_list must return vectors with two entries. In our case the function is very simple, it just returns 1 for the real part \(v\) and 0 for the imaginary part \(w\) regardless of the point where it is evaluated.

ParameterReader classThe next class is responsible for preparing the ParameterHandler object and reading parameters from an input file. It includes a function declare_parameters that declares all the necessary parameters and a read_parameters function that is called from outside to initiate the parameter reading process.

The constructor stores a reference to the ParameterHandler object that is passed to it:

ParameterReader::declare_parametersThe declare_parameters function declares all the parameters that our ParameterHandler object will be able to read from input files, along with their types, range conditions and the subsections they appear in. We will wrap all the entries that go into a section in a pair of braces to force the editor to indent them by one level, making it simpler to read which entries together form a section:

Parameters for mesh and geometry include the number of global refinement steps that are applied to the initial coarse mesh and the focal distance \(d\) of the transducer lens. For the number of refinement steps, we allow integer values in the range \([0,\infty)\), where the omitted second argument to the Patterns::Integer object denotes the half-open interval. For the focal distance any number greater than zero is accepted:

The next subsection is devoted to the physical parameters appearing in the equation, which are the frequency \(\omega\) and wave speed \(c\). Again, both need to lie in the half-open interval \([0,\infty)\) represented by calling the Patterns::Double class with only the left end-point as argument:

Last but not least we would like to be able to change some properties of the output, like filename and format, through entries in the configuration file, which is the purpose of the last subsection:

Since different output formats may require different parameters for generating output (like for example, postscript output needs viewpoint angles, line widths, colors etc), it would be cumbersome if we had to declare all these parameters by hand for every possible output format supported in the library. Instead, each output format has a FormatFlags::declare_parameters function, which declares all the parameters specific to that format in an own subsection. The following call of DataOutInterface<1>::declare_parameters executes declare_parameters for all available output formats, so that for each format an own subsection will be created with parameters declared for that particular output format. (The actual value of the template parameter in the call, <1> above, does not matter here: the function does the same work independent of the dimension, but happens to be in a template-parameter-dependent class.) To find out what parameters there are for which output format, you can either consult the documentation of the DataOutBase class, or simply run this program without a parameter file present. It will then create a file with all declared parameters set to their default values, which can conveniently serve as a starting point for setting the parameters to the values you desire.

ParameterReader::read_parametersThis is the main function in the ParameterReader class. It gets called from outside, first declares all the parameters, and then reads them from the input file whose filename is provided by the caller. After the call to this function is complete, the prm object can be used to retrieve the values of the parameters read in from the file :

ComputeIntensity classAs mentioned in the introduction, the quantity that we are really after is the spatial distribution of the intensity of the ultrasound wave, which corresponds to \(|u|=\sqrt{v^2+w^2}\). Now we could just be content with having \(v\) and \(w\) in our output, and use a suitable visualization or postprocessing tool to derive \(|u|\) from the solution we computed. However, there is also a way to output data derived from the solution in deal.II, and we are going to make use of this mechanism here.

So far we have always used the DataOut::add_data_vector function to add vectors containing output data to a DataOut object. There is a special version of this function that in addition to the data vector has an additional argument of type DataPostprocessor. What happens when this function is used for output is that at each point where output data is to be generated, the DataPostprocessor::evaluate_scalar_field() or DataPostprocessor::evaluate_vector_field() function of the specified DataPostprocessor object is invoked to compute the output quantities from the values, the gradients and the second derivatives of the finite element function represented by the data vector (in the case of face related data, normal vectors are available as well). Hence, this allows us to output any quantity that can locally be derived from the values of the solution and its derivatives. Of course, the ultrasound intensity \(|u|\) is such a quantity and its computation doesn't even involve any derivatives of \(v\) or \(w\).

In practice, the DataPostprocessor class only provides an interface to this functionality, and we need to derive our own class from it in order to implement the functions specified by the interface. In the most general case one has to implement several member functions but if the output quantity is a single scalar then some of this boilerplate code can be handled by a more specialized class, DataPostprocessorScalar and we can derive from that one instead. This is what the ComputeIntensity class does:

In the constructor, we need to call the constructor of the base class with two arguments. The first denotes the name by which the single scalar quantity computed by this class should be represented in output files. In our case, the postprocessor has \(|u|\) as output, so we use "Intensity".

The second argument is a set of flags that indicate which data is needed by the postprocessor in order to compute the output quantities. This can be any subset of update_values, update_gradients and update_hessians (and, in the case of face data, also update_normal_vectors), which are documented in UpdateFlags. Of course, computation of the derivatives requires additional resources, so only the flags for data that are really needed should be given here, just as we do when we use FEValues objects. In our case, only the function values of \(v\) and \(w\) are needed to compute \(|u|\), so we're good with the update_values flag.

The actual postprocessing happens in the following function. Its input is an object that stores values of the function (which is here vector-valued) representing the data vector given to DataOut::add_data_vector, evaluated at all evaluation points where we generate output, and some tensor objects representing derivatives (that we don't use here since \(|u|\) is computed from just \(v\) and \(w\)). The derived quantities are returned in the computed_quantities vector. Remember that this function may only use data for which the respective update flag is specified by get_needed_update_flags. For example, we may not use the derivatives here, since our implementation of get_needed_update_flags requests that only function values are provided.

The computation itself is straightforward: We iterate over each entry in the output vector and compute \(|u|\) from the corresponding values of \(v\) and \(w\):

UltrasoundProblem classFinally here is the main class of this program. It's member functions are very similar to the previous examples, in particular step-4, and the list of member variables does not contain any major surprises either. The ParameterHandler object that is passed to the constructor is stored as a reference to allow easy access to the parameters from all functions of the class. Since we are working with vector valued finite elements, the FE object we are using is of type FESystem.

The constructor takes the ParameterHandler object and stores it in a reference. It also initializes the DoF-Handler and the finite element system, which consists of two copies of the scalar Q1 field, one for \(v\) and one for \(w\):

UltrasoundProblem::make_gridHere we setup the grid for our domain. As mentioned in the exposition, the geometry is just a unit square (in 2d) with the part of the boundary that represents the transducer lens replaced by a sector of a circle.

First we generate some logging output and start a timer so we can compute execution time when this function is done:

Then we query the values for the focal distance of the transducer lens and the number of mesh refinement steps from our ParameterHandler object:

Next, two points are defined for position and focal point of the transducer lens, which is the center of the circle whose segment will form the transducer part of the boundary. Notice that this is the only point in the program where things are slightly different in 2D and 3D. Even though this tutorial only deals with the 2D case, the necessary additions to make this program functional in 3D are so minimal that we opt for including them:

As initial coarse grid we take a simple unit square with 5 subdivisions in each direction. The number of subdivisions is chosen so that the line segment \([0.4,0.6]\) that we want to designate as the transducer boundary is spanned by a single face. Then we step through all cells to find the faces where the transducer is to be located, which in fact is just the single edge from 0.4 to 0.6 on the x-axis. This is where we want the refinements to be made according to a circle shaped boundary, so we mark this edge with a different manifold indicator. Since we will Dirichlet boundary conditions on the transducer, we also change its boundary indicator.

For the circle part of the transducer lens, a SphericalManifold object is used (which, of course, in 2D just represents a circle), with center computed as above.

Now global refinement is executed. Cells near the transducer location will be automatically refined according to the circle shaped boundary of the transducer lens:

Lastly, we generate some more logging output. We stop the timer and query the number of CPU seconds elapsed since the beginning of the function:

UltrasoundProblem::setup_systemInitialization of the system matrix, sparsity patterns and vectors are the same as in previous examples and therefore do not need further comment. As in the previous function, we also output the run time of what we do here:

UltrasoundProblem::assemble_systemAs before, this function takes care of assembling the system matrix and right hand side vector:

First we query wavespeed and frequency from the ParameterHandler object and store them in local variables, as they will be used frequently throughout this function.

As usual, for computing integrals ordinary Gauss quadrature rule is used. Since our bilinear form involves boundary integrals on \(\Gamma_2\), we also need a quadrature rule for surface integration on the faces, which are \(dim-1\) dimensional:

The FEValues objects will evaluate the shape functions for us. For the part of the bilinear form that involves integration on \(\Omega\), we'll need the values and gradients of the shape functions, and of course the quadrature weights. For the terms involving the boundary integrals, only shape function values and the quadrature weights are necessary.

As usual, the system matrix is assembled cell by cell, and we need a matrix for storing the local cell contributions as well as an index vector to transfer the cell contributions to the appropriate location in the global system matrix after.

On each cell, we first need to reset the local contribution matrix and request the FEValues object to compute the shape functions for the current cell:

At this point, it is important to keep in mind that we are dealing with a finite element system with two components. Due to the way we constructed this FESystem, namely as the Cartesian product of two scalar finite element fields, each shape function has only a single nonzero component (they are, in deal.II lingo, primitive). Hence, each shape function can be viewed as one of the \(\phi\)'s or \(\psi\)'s from the introduction, and similarly the corresponding degrees of freedom can be attributed to either \(\alpha\) or \(\beta\). As we iterate through all the degrees of freedom on the current cell however, they do not come in any particular order, and so we cannot decide right away whether the DoFs with index \(i\) and \(j\) belong to the real or imaginary part of our solution. On the other hand, if you look at the form of the system matrix in the introduction, this distinction is crucial since it will determine to which block in the system matrix the contribution of the current pair of DoFs will go and hence which quantity we need to compute from the given two shape functions. Fortunately, the FESystem object can provide us with this information, namely it has a function FESystem::system_to_component_index, that for each local DoF index returns a pair of integers of which the first indicates to which component of the system the DoF belongs. The second integer of the pair indicates which index the DoF has in the scalar base finite element field, but this information is not relevant here. If you want to know more about this function and the underlying scheme behind primitive vector valued elements, take a look at step-8 or the Handling vector valued problems module, where these topics are explained in depth.

If both DoFs \(i\) and \(j\) belong to same component, i.e. their shape functions are both \(\phi\)'s or both \(\psi\)'s, the contribution will end up in one of the diagonal blocks in our system matrix, and since the corresponding entries are computed by the same formula, we do not bother if they actually are \(\phi\) or \(\psi\) shape functions. We can simply compute the entry by iterating over all quadrature points and adding up their contributions, where values and gradients of the shape functions are supplied by our FEValues object.

You might think that we would have to specify which component of the shape function we'd like to evaluate when requesting shape function values or gradients from the FEValues object. However, as the shape functions are primitive, they have only one nonzero component, and the FEValues class is smart enough to figure out that we are definitely interested in this one nonzero component.

We also have to add contributions due to boundary terms. To this end, we loop over all faces of the current cell and see if first it is at the boundary, and second has the correct boundary indicator associated with \(\Gamma_2\), the part of the boundary where we have absorbing boundary conditions:

These faces will certainly contribute to the off-diagonal blocks of the system matrix, so we ask the FEFaceValues object to provide us with the shape function values on this face:

Next, we loop through all DoFs of the current cell to find pairs that belong to different components and both have support on the current face:

The check whether shape functions have support on a face is not strictly necessary: if we don't check for it we would simply add up terms to the local cell matrix that happen to be zero because at least one of the shape functions happens to be zero. However, we can save that work by adding the checks above.

In either case, these DoFs will contribute to the boundary integrals in the off-diagonal blocks of the system matrix. To compute the integral, we loop over all the quadrature points on the face and sum up the contribution weighted with the quadrature weights that the face quadrature rule provides. In contrast to the entries on the diagonal blocks, here it does matter which one of the shape functions is a \(\psi\) and which one is a \(\phi\), since that will determine the sign of the entry. We account for this by a simple conditional statement that determines the correct sign. Since we already checked that DoF \(i\) and \(j\) belong to different components, it suffices here to test for one of them to which component it belongs.

Now we are done with this cell and have to transfer its contributions from the local to the global system matrix. To this end, we first get a list of the global indices of the this cells DoFs...

...and then add the entries to the system matrix one by one:

The only thing left are the Dirichlet boundary values on \(\Gamma_1\), which is characterized by the boundary indicator 1. The Dirichlet values are provided by the DirichletBoundaryValues class we defined above:

UltrasoundProblem::solveAs already mentioned in the introduction, the system matrix is neither symmetric nor definite, and so it is not quite obvious how to come up with an iterative solver and a preconditioner that do a good job on this matrix. We chose instead to go a different way and solve the linear system with the sparse LU decomposition provided by UMFPACK. This is often a good first choice for 2D problems and works reasonably well even for a large number of DoFs. The deal.II interface to UMFPACK is given by the SparseDirectUMFPACK class, which is very easy to use and allows us to solve our linear system with just 3 lines of code.

Note again that for compiling this example program, you need to have the deal.II library built with UMFPACK support.

The code to solve the linear system is short: First, we allocate an object of the right type. The following initialize call provides the matrix that we would like to invert to the SparseDirectUMFPACK object, and at the same time kicks off the LU-decomposition. Hence, this is also the point where most of the computational work in this program happens.

After the decomposition, we can use A_direct like a matrix representing the inverse of our system matrix, so to compute the solution we just have to multiply with the right hand side vector:

UltrasoundProblem::output_resultsHere we output our solution \(v\) and \(w\) as well as the derived quantity \(|u|\) in the format specified in the parameter file. Most of the work for deriving \(|u|\) from \(v\) and \(w\) was already done in the implementation of the ComputeIntensity class, so that the output routine is rather straightforward and very similar to what is done in the previous tutorials.

Define objects of our ComputeIntensity class and a DataOut object:

Next we query the output-related parameters from the ParameterHandler. The DataOut::parse_parameters call acts as a counterpart to the DataOutInterface<1>::declare_parameters call in ParameterReader::declare_parameters. It collects all the output format related parameters from the ParameterHandler and sets the corresponding properties of the DataOut object accordingly.

Now we put together the filename from the base name provided by the ParameterHandler and the suffix which is provided by the DataOut class (the default suffix is set to the right type that matches the one set in the .prm file through parse_parameters()):

The solution vectors \(v\) and \(w\) are added to the DataOut object in the usual way:

For the intensity, we just call add_data_vector again, but this with our ComputeIntensity object as the second argument, which effectively adds \(|u|\) to the output data:

The last steps are as before. Note that the actual output format is now determined by what is stated in the input file, i.e. one can change the output format without having to re-compile this program:

UltrasoundProblem::runHere we simply execute our functions one after the other:

main functionFinally the main function of the program. It has the same structure as in almost all of the other tutorial programs. The only exception is that we define ParameterHandler and ParameterReader objects, and let the latter read in the parameter values from a textfile called step-29.prm. The values so read are then handed over to an instance of the UltrasoundProblem class:

The current program reads its run-time parameters from an input file called step-29.prm that looks like this:

As can be seen, we set \(d=0.3\), which amounts to a focus of the transducer lens at \(x=0.5\), \(y=0.3\). The coarse mesh is refined 5 times, resulting in 160x160 cells, and the output is written in vtu format. The parameter reader understands many more parameters pertaining in particular to the generation of output, see the explanation in step-19, but we need none of these parameters here and therefore stick with their default values.

Here's the console output of the program in debug mode:

(Of course, execution times will differ if you run the program locally.) The fact that most of the time is spent on assembling the system matrix and generating output is due to the many assertions that need to be checked in debug mode. In release mode these parts of the program run much faster whereas solving the linear system is hardly sped up at all:

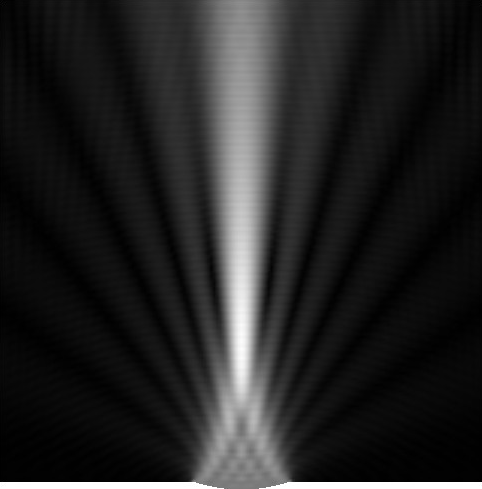

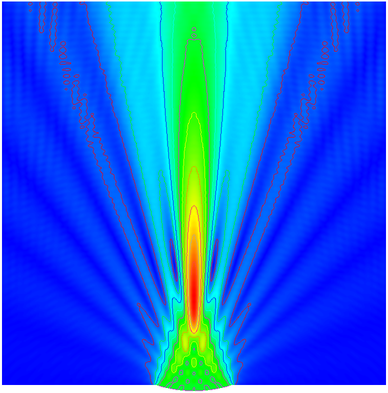

The graphical output of the program looks as follows:

|

|

| |

The first two pictures show the real and imaginary parts of \(u\), whereas the last shows the intensity \(|u|\). One can clearly see that the intensity is focused around the focal point of the lens (0.5, 0.3), and that the focus is rather sharp in \(x\)-direction but more blurred in \(y\)-direction, which is a consequence of the geometry of the focusing lens, its finite aperture, and the wave nature of the problem.

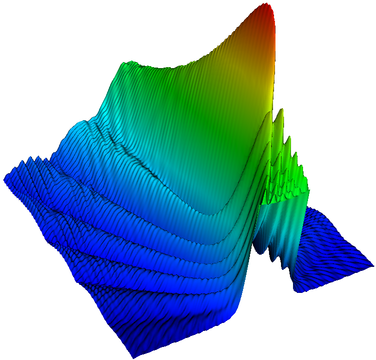

Because colorful graphics are always fun, and to stress the focusing effects some more, here is another set of images highlighting how well the intensity is actually focused in \(x\)-direction:

|

|

As a final note, the structure of the program makes it easy to determine which parts of the program scale nicely as the mesh is refined and which parts don't. Here are the run times for 5, 6, and 7 global refinements:

Each time we refine the mesh once, so the number of cells and degrees of freedom roughly quadruples from each step to the next. As can be seen, generating the grid, setting up degrees of freedom, assembling the linear system, and generating output scale pretty closely to linear, whereas solving the linear system is an operation that requires 8 times more time each time the number of degrees of freedom is increased by a factor of 4, i.e. it is \({\cal O}(N^{3/2})\). This can be explained by the fact that (using optimal ordering) the bandwidth of a finite element matrix is \(B={\cal O}(N^{(dim-1)/dim})\), and the effort to solve a banded linear system using LU decomposition is \({\cal O}(BN)\). This also explains why the program does run in 3d as well (after changing the dimension on the UltrasoundProblem object), but scales very badly and takes extraordinary patience before it finishes solving the linear system on a mesh with appreciable resolution, even though all the other parts of the program scale very nicely.

An obvious possible extension for this program is to run it in 3d — after all, the world around us is three-dimensional, and ultrasound beams propagate in three-dimensional media. You can try this by simply changing the template parameter of the principal class in main() and running it. This won't get you very far, though: certainly not if you do 5 global refinement steps as set in the parameter file. You'll simply run out of memory as both the mesh (with its \((2^5)^3 \cdot 5^3=2^{15}\cdot 125 \approx 4\cdot 10^6\) cells) and in particular the sparse direct solver take too much memory. You can solve with 3 global refinement steps, however, if you have a bit of time: in early 2011, the direct solve takes about half an hour. What you'll notice, however, is that the solution is completely wrong: the mesh size is simply not small enough to resolve the solution's waves accurately, and you can see this in plots of the solution. Consequently, this is one of the cases where adaptivity is indispensable if you don't just want to throw a bigger (presumably parallel) machine at the problem.

1.8.14

1.8.14